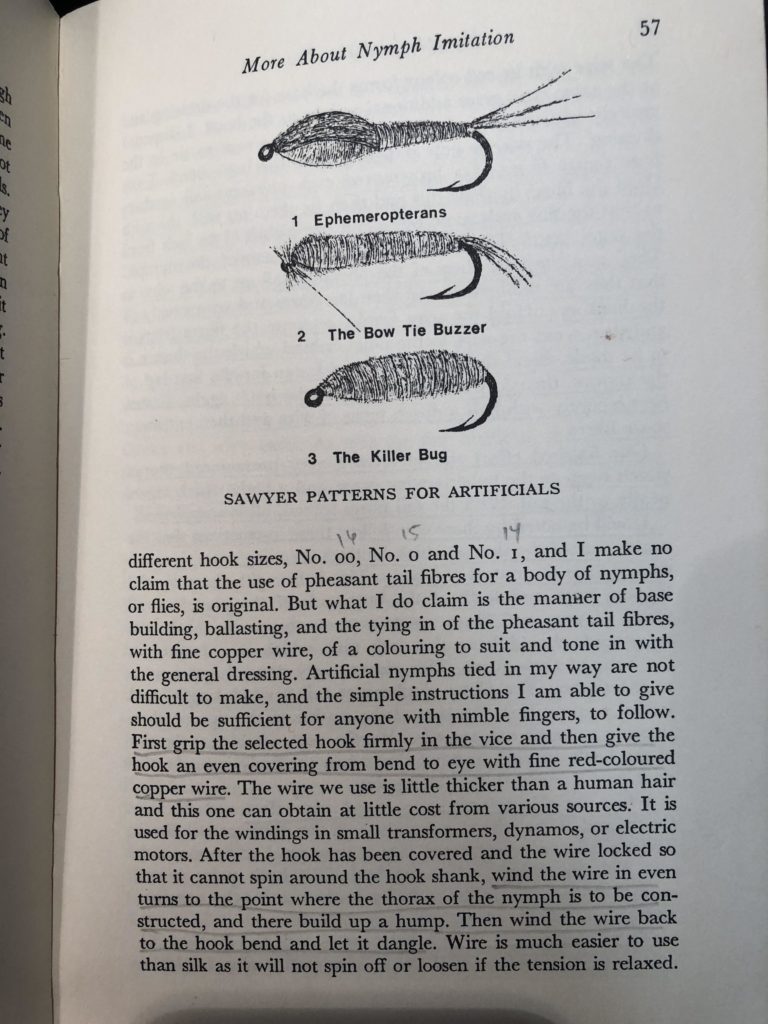

Original Frank Sawyer Killer Bug Fly Tying Recipe: Hooks of size 10, 12, or 14, Chadwick’s 477 Wool, and redish fine wire

Wind the wire starting at the bend to the eye and back again, leaving wire dangling at the bend.

Starting at the eye (if doing one covering of wool), lap the wool along the wire covered shank and stop at the bend. One or two coverings is usually all that is required, stopping at the bend.

Take the wire and secure the end of the wool with three turns and trim .

___________________________

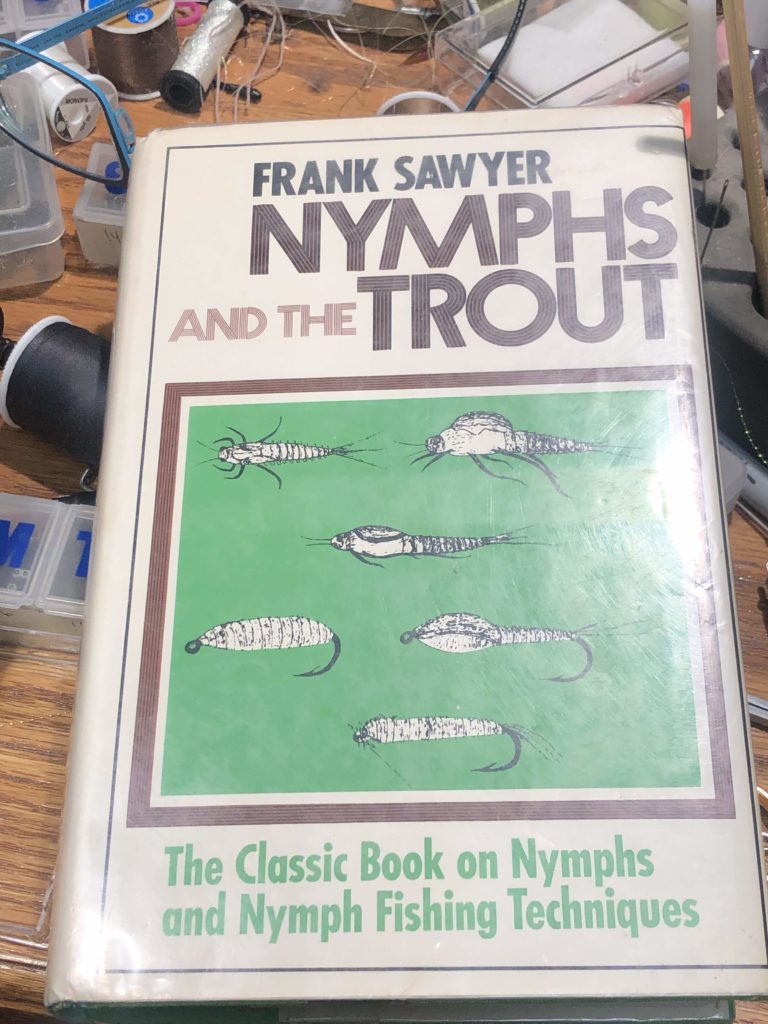

Probably one of the most famous and oft copied flies in the world is Frank Sawyer’s Pheasant Tail. However, Sawyer fished with three flies the PT, his Grey Goose and his Killer Bug (his tying descriptions for all three flies are in the photographs below), which is also not counting his Bow Tie Buzzard for midges and the Swedish Special for Northern Sweden, all strokes of genius using copper wire.

Sawyer’s Killer Bug or Sawyer’s Grayling Killer Bug, as it might have been originally called by some, is a very productive fly and is simple to tie, my favorite kind of general purpose fly. It was tied in very large sizes and he caught salmon with it. In smaller sizes, it was used for trout, and it was known primarily as a grayling fly.

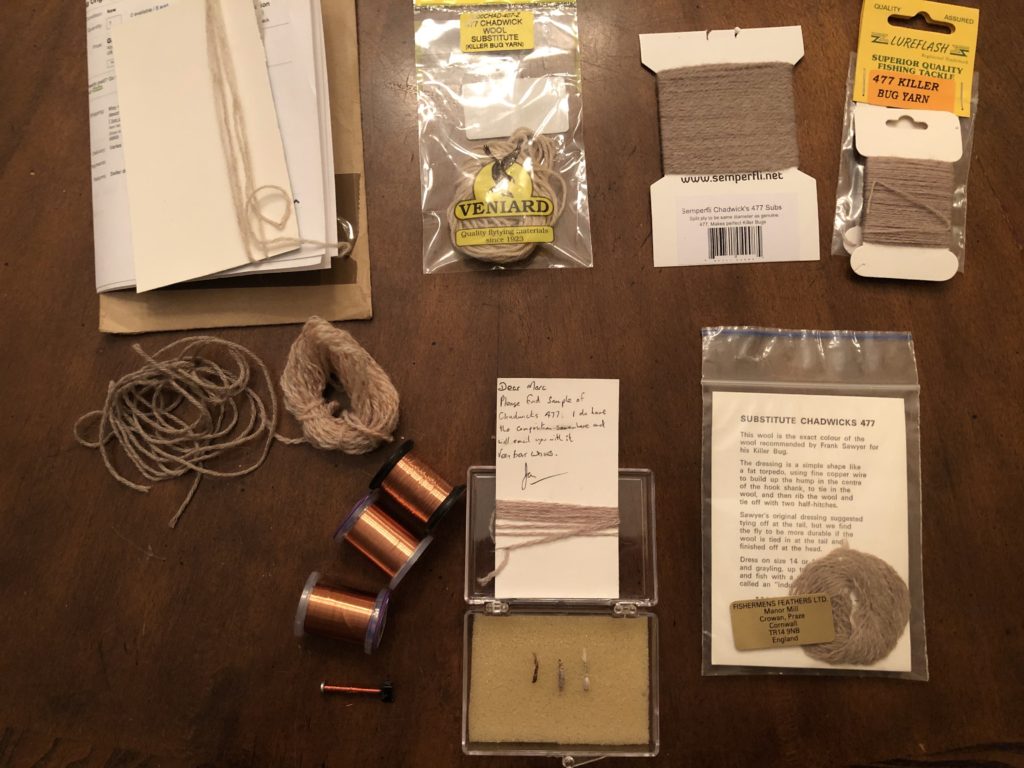

The only problem with it, is that the yarn used to tie it, has been discontinued since 1965 and it still has a mystical following among fly tiers, so any remnants of it are often gobbled up. Some call trying to collect Chadwick’s 477, as a hobby within a hobby. I often use the Killer Bug combined with an RS2 in a two-fly rig. Frank Sawyer’s grandson, Nick, has become a good pen pal friend of mine some 20 years ago.

It simply requires knitting yarn, some copper wire and a hook. Frank Sawyer used to tie these flies without a vice, simply holding the hook in one hand and the material in the other. This fly developed a reputation as a grayling killer bug, whereas his pheasant tail nymph was more often the one chosen for trout, but I have found that it works well on grayling, trout, and even Alaskan or Kokanee salmon. His grandson, Nick Sawyer, who was a special forces Captain in the Royal Services, when I met him and also moonlighted at times, offering his grandfather’s Sawyer Nymphs, has moved on to bigger and better things as Brigadier of their special forces. The killer bug fly imitates the gammarus pulex or what we commonly refer to as a scud but also seems to be taken for an egg pattern in the smaller sizes or a crane fly larva.

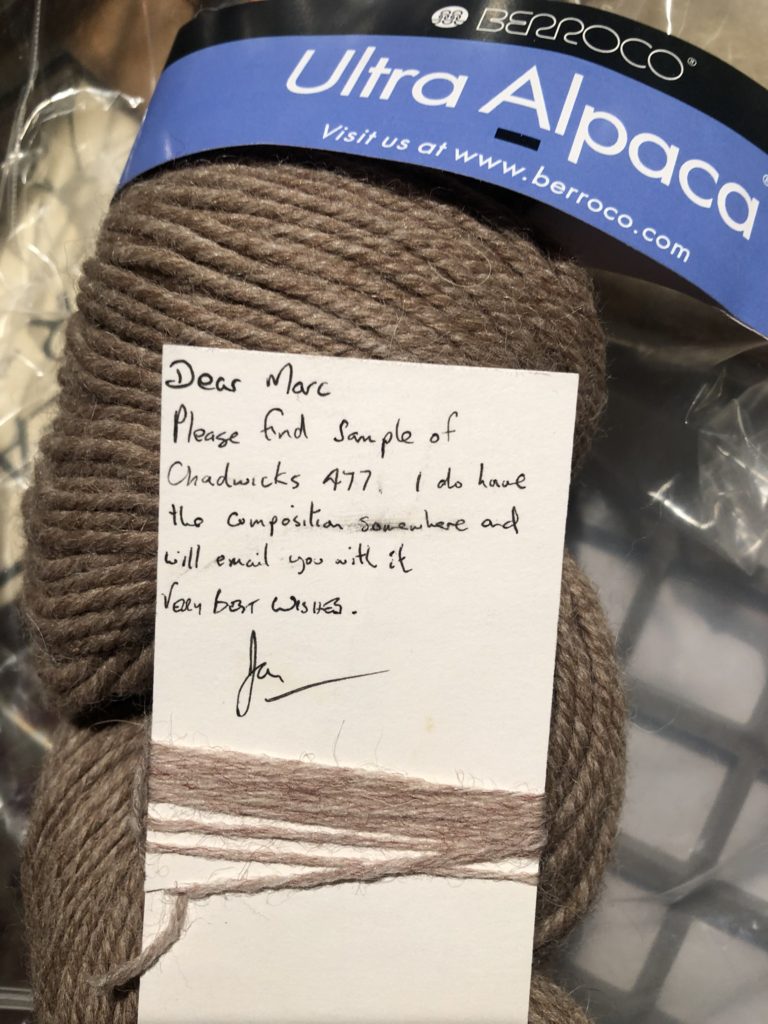

Frank Sawyer tied his fly with a yarn that is no longer produced – Chadwick’s 477, which he wife used for darning wool socks. That yarn is now one of those legendary fly tying materials that has achieve a mythical status, along with polar bear hair, seal fur, and urine-stained fox fur. Chadwick’s 477 hasn’t been produced for probably 40 years now and when the rare card is not handed down in someone’s will it sells at auction for over 100 quid. Nick was gracious enough to send some flies that his late grandfather had tied. Ian Moutter, the famous English angling author, also became a pen pal and was kind to send me a small card of Chadwick’s 477 wool.

Fortunately for those of us without ancestors with foresight, there are substitutes. But the search for perfection is a long road to follow when looking for substitutes of Chadwick’s 477. Veniard “killer bug yarn” is one and Lureflash 477, both also difficult to find. Nick says, “The Lureflash wool is excellent – almost as good as the original Chadwicks.”

There is also a new one out now, by Semperfli, which I haven’t yet tested, but I am sure Nick would love the name of the brand. They claim, “This new ‘477’ has been specially developed to replicate as close as possible to the classic Sawyer Bug tying wool. Originally Sawyer used Chadwick 477 and though perfectionists found other substitutes, they simply did not match the original material for color. The Semperfli team had their Chadwick’s 477 substitute spec’ed to match the original! It comes as a 3 ply, making tying of the nice thick Sawyer Killer Bug a cinch. To perfectly replicate the original Killer Bug simply split the 477 Substitute from 3 ply to one and it matches the diameter of the original 477.” Interesting claim, as the original 477 was two ply, not one but at any rate, it’s not a bad color.

Chris Helm’s Whitetail Fly Tieing Supplies carries a “Chadwicks 477 Yarn” substitute that is marketed by Lathkill Fly Fishing in the UK. I’ve also had success with rummaging through yarn and craft stores with my Frank Sawyer’s original killer bug and small strand of Chadwick’s yarn given to me by Nick many years ago. Sawyer said, “The successful attraction of this pattern is due to the fact that the particular ‘darning wool’ used, completely changes colour when wet.” Chadwick’s 477 is a fawn color, kind of a greyish brown, but it has red fibers scattered through it, and when the yarn is wet, the red fibers gave the yarn a pinkish tan hue.

The Veniard yarn and the Lathkill yarn, remains more tan than pinkish when wet, so it is not as good as the Chadwick’s or Lureflash. Any yarn may work, as many suggest, but I believe that the killer attraction of the original is due to the color.

Some say that Jamieson’s Shetland Spindrift in the Sand color can also be died with a Sand color Prismacolor marking pen, and turns a definite pinkish tan when wet, which appears to me, having bought some it, is a very close imitation to the original but a bit too tan.

Another substitute I have tried is “Berroco Ultra Alpaca Fine”, color #1214 (“Steel Cut Oats”), dye lot #2J9711. [Note: this is not the same as Berroco “Ultra Alpaca”, “Ultra Alpaca Chunky” or “Ultra Alpaca Light” yarns] which is close enough in color when wet. Frank Sawyer added, unintentionally to the mythical properties, when he wrote that he had tried many other yarns, but none were so effective as the Chadwick’s 477. He went on to describe the color changing properties to a pinkish hue and the fact that the part nylon yet high content of wool in the yarn, seemed to contribute to its success.

The fly is tied solely with copper wire and no tying thread. The copper wire provides a little bit of extra weight, but not nearly as much as a lead underbody or even a beadhead. Sawyer used a varnished copper wire that had a slightly reddish brown color, but it seems you can’t get that color anymore. I use old telephone wires (the kind you use to connect the phone to the wall) separated for this purpose, which take on this reddish patina with age and exposure to the air.

Sawyer wrote in Nymphs and the Trout (1958) about the wire for tying Killer Bugs: To make this bug, grip the hook firmly in the vice and then give the hook a double even covering of wire, colour of this not important but normally we now use red.” He also notes the wire for the Killer Bug is thicker than the “human

A dead-drift approach is the usual technique, but fish can also take the fly as it swings to the surface and I know some who like to give the fly action with quick tugs, a technique I have found unnecessary on trout, but haven’t enough experience with chalk stream grayling to say if it is necessary with those. Keep in mind that no lead was used on the line by Sawyer, so if you are using these Killer Bugs in the traditional American nymphing fashion, you have to adjust accordingly, as they are quite heavily weighted nymphs with the two full wraps of copper wire as the underbody.

Nick wrote a letter to me, “If only Chadwicks knew the trouble they had caused! Below are some facts:

Chadwicks ceased production of 477 in around 1965. Frank did indeed have a substitute made by an American he met on the river bank. This same gentlemen still provides me with the substitute wool. It is the colour of the wool when wet which is important and this is affected by the colour and thickness of the copper wire beneath the wool. The colour of the wool is reasonably important but by far the most important element of the Killer Bug is the manner in which it is fished. I have tried many substitutes of suitable colour but the main problem has been the fibres rather than the colour – it is important to have the right thickness and the correct mix of natural to artificial fibres. I have no idea what the correct ratio should be, but high levels of artificial fibres make for a poor Killer Bug.

Here is a handy guide for Killer Bug fishermen:

1. Get the technique right – it is possible to catch fish on a bare hook if fished in a natural manner.

2. Get the weight of the Killer Bug right – it should sink quickly but not so quickly that the current doesn’t affect it.

3. The wool covering should be 2-3 layers only so that the copper wire beneath the wool gives the Killer Bug a translucent appearance when wet.

4. It doesn’t matter what colour the dry wool is, but when wet and wound over copper wire it should be grey/brown with a slight pink tinge.

5. Did I mention to get the technique right!

Killer Bugs made with the substitute wool and a booklet on the correct Killer Bug technique are available from my website www.sawyernymphs.com [ed.-which is no longer in existence, but the flies were then sold through http://www.hartleyfly.com/cgi-bin/sitewise.pl also seemingly a bad link now]

Tight Lines,

Nick Sawyer

The actual tying techniques are set forth best in Frank Sawyer’s books, rather than the infinite number of variations available on the Internet.

Killer Bug Nymph

Killer Bug Nymph

Hook: straight-shank wet round bend hooks (barbed) down-eyed (the Tiemco 3761 or 100 seem similar to me, although Sawyer didn’t discuss his favorite hooks, lending to my belief it doesn’t really matter that a reasonable choice will do)

Thread/weight: fine dark coloured (enamelled) copper wire [note it is not a copper-ribbed body, as many have wrongfully done in copying the pattern, although it appears that way in some photos as the Chadwick’s yarn has a copper color flash to some of the fibers in it]

Tail/abdomen/thorax/wingcase: copper wire and a substitute Chadwick’s 477 wool See this comparison of wools below and another at https://www.flyfishing.co.uk/fly-tying-forum/53821-chadwicks-477-a-2.html\

I recently ordered the Veniard subsitute, that of Semperfli and the Jamieson’s Shetland Spindrift Yarns (290 oyster color), used by many to tie the Killer Bug and Utah Killer Bug. I have also recently tried to acquire some Berroco Ultra Alpaca Fine #1214 Yarn Steel Cut Oats. I’ll let you all know how these substitutes compare to the original Chadwick’s 477.

Production of this original 85% wool / 15% nylon blend Chadwick’s 477 “Wool and Nylon for Reinforcing and Mending” ceased in 1965. This is original Chadwicks 477 wool and nylon blend and is not a substitute or copy of it.

Substitutes ARE available from Semperfli, Veniard, Paton (their Classic Wool Yarn [00229] Natural Mix) and Mackenzie-Phillips, amongst others… and the fish maybe can’t tell the difference, but…then again maybe the color is an important part of this magical combination, as Nick says it is.

The grayling killer bug was developed in the 1930’s when he worked as a river keeper on the River Avon. One of his tasks was to rid the river of grayling. The fly he developed, which imitates the tiny 20mm gammarus pulex flea-like freshwater shrimp aka scud, was hugely successful. He also wrote of its success on trout in lakes.

They are sought out by trout and salmon, parr, bullheads and stone loach, minnows and sticklebacks, and it is a widely available and important food both in still-waters and rivers. This is helped by their being quite like crane fly larvae, the hatching sedge or caddis fly – and that may be what the trout are taking these fly for.

Sawyer himself reckoned the attraction of this fly is because the particular ‘darning wool’ used completely changes colour when wet. Chadwick’s 477 is a fawn color, a greyish-brown, but it has red fibers running through it. When the yarn gets wet, the red fibers give it a pinkish tan hue. This and the copper wire used to tie it (which gives weight or ‘heft’ as well…) makes it look just right to the fish.

The wool came in at least two different size cards. The smaller card 10.5 cm x 6cm with a has much less wool than the larger card 12cm x 7cm

___________________________________________________

There is a great thread about the thread (pardon the pun), on http://classicflyrodforum.com/forum/viewtopic.php?f=73&t=94764.

I believe that the best substitute is the FISHERMENS FEATHERS, CORNWALL ENGLAND, SUBSTITUTE CHADWICKS 477 which has also been discontinued for over 50 years, and I believe was the substitute that Frank Sawyer and his wife were using for many decades after the Chadwick’s 477 was no longer available. There are many others around, but none so close in coloration as this one, although I will discuss the others.

Norm was kind enough to send me some of his Berroco yarn, which is also outstanding as a replica of Chadwick’s 477, but sadly also out of production for some time now.

“THE PINKY grey colour which is so attractive to grayling, and was championed by Frank Sawyer and his Killer Bug, is an extremely difficult colour to reproduce, especially now that supplies of the Chadwick’s 477 yarn, originally used by Sawyer and discontinued long ago, have dwindled away, swallowed up and secreted in the dusty cabinets of the angling memorabilia collector.

Luckily, the astute Mrs. Sawyer, who continued to tie her husband’s flies after his death, invested in a substitute: a thin, three-ply wool possessing the same deadly hue- She bought it in bulk, which was a master stroke because times change quickly and the woollen industry once again recognised that the nondescript ashy pink was not a popular colour in the fashion world, and discontinued this tine as well.

Recently, Ellis Slater bought up all the remaining substitute that Mrs. Sawyer had left, and is now retailing it at 50p per pack (about 7 ½ yards (6 m) ). – A sirnple product, and a very simple fly, but a fly that requires exact coloration. Dare you go grayling fishing without any?”

From what I understand, Frank Sawyer died in 1980, so it would appear that the Killer Bugs that Mrs. Sawyer tied from (at least) 1980 onwards were tied on the substitute yarn that Mrs. Sawyer had purchased …. and that substitute was also discontinued.

So, it would appear that both of the yarns tied / used by the Sawyers have been discontinued and that many of the actual Killer Bugs tied by the Sawyers (at least after 1980) did not use the Chadwicks 477 yarn.

On Fishing the Killer Bug from Nick Sawyer:

Frank Sawyer’s Killer Bug is deadly on chalk streams. Although designed for catching large numbers of grayling, it can also be effective against trout. The Killer Bug technique is unique, but can be learnt quickly by anyone who is willing to learn.

As far as I am aware, no one is really sure why the Killer Bug is so effective. My grandfather, the late Frank Sawyer, originally designed it to imitate the freshwater shrimp Gammarus Pulex, but it is just as effective in water without the crustacean, or when tied several times larger than is natural. The Killer Bug is usually taken when it is made to ‘swim’. More often than not this will be in the ‘shrimp zone’ but it can sometimes be taken above this area while apparently ‘swimming’ to the surface. As shrimp only inhabit the bottom part of a chalk stream it is difficult to see why the fish would take an artificial shrimp in the wrong place. Pigs may fly, but who would eat a bacon sandwich if it was floating several inches above the table? My grandfather suggested in ‘Nymphs and the Trout’ that the swimming bug resembled a hatching sedge making its way to the surface. Some quite well known fishermen claim the Killer Bug looks like a maggot or a grub that has fallen into the water, others say it looks like a food pellet to stocked fish. I have even seen small pike follow a Killer Bug through the water (although never take) so perhaps it resembles a small fish under some conditions.

The widely reported chalk stream malaise and decline in fly abundance is a definite cause for concern, but we sometimes forget that perhaps up to 80% of a trout’s food is taken sub-surface. Unless we are lucky enough to be fishing during a hatch, the trout may not be that interested in dry fly. This presents a problem. Like most fishermen, I fish when I can find the time, hatch or no hatch. Fortunately fish have to eat. If there is no surface fly, or they seem to be ignoring any fly and hatching nymph that are present, then they must be eating something else. It is often the freshwater shrimp.

It is always amazing how often fishermen fail to spot the huge number of clearly discernible fish in a stretch of water. The first step in Killer Bug fishing is to try and operate where the fish are visible. It is not essential, but it makes the technique easier and much more fun.

The Upper Avon, where I enjoy most of my fishing, has a grayling population that far exceeds that of trout. It is very tempting to ignore the grayling and keep moving upstream on the hunt for trout. My grandfather had a phrase for this: “Giving up gold to fish for tinsel.” Grayling are a true wild fish and a joy to catch. Not only do they provide worthy sport, but they taste good and are more plentiful than trout. On many occasions I have been fishing for grayling and a previously hidden trout has darted out of cover to take my Killer Bug. For the out-of-practice fisherman, or those of us who fish infrequently, grayling are an ideal way to start the day and polish up those Killer Bug skills before tackling the big trout a few hundred metres upstream. My father and I sometimes make a day out of grayling fishing with a Killer Bug. The goal is to catch every single grayling in a shoal before moving on. It is not unusual for us to land well over 50 grayling in 3 or 4 hours of fishing.

The most important part of the Killer Bug technique is making the bug swim in the correct manner at the right place. To achieve this, the bug must be allowed to sink to the bottom part of the river and then made to swim up to the surface in a smooth, natural manner. Where to start the swimming motion will depend on the location of the fish and the current flow. The point at which the swimming motion commences is known as the activation point. The cast has to be made far enough up stream of the activation point so the bug can sink to the right depth before the swimming motion is started. This point is known as the cast area. Here’s the good bit. As long as there are no weeds or obstructions, the bug can bounce along the bottom for some distance before commencing the swimming motion. This reduces the requirement for accurate and delicate casting as anywhere upstream of the cast area will be satisfactory. All the fisherman has to do is allow the bug to bounce along the river bed until it reaches the activation point and then start the swimming motion by slowly lifting the rod tip and maintaining a tight line. The peculiarities of weed, obstructions and currents can occasionally prevent the fisherman from carrying out this technique, and fish have a habit of feeding in awkward places, but there will be many locations on the chalk stream where this technique can be used. Trout can sometimes be startled by a bug rolling along the river bed but grayling are hardly ever troubled.

The activation point is easy to calculate. To be most effective the Bug should be made to start swimming 1 to 2 feet in front of the target fish. This makes the activation point 2 feet in front of the target fish if it is located at the bottom of the river, or further upstream if it is feeding nearer the surface. The cast area will depend completely on water depth and current speed. Unless it is a particularly deep pool or a very fast current, 4 feet is a good starting point, but trial and error will ultimately be the deciding factor. If it is clear that the bug has not sunk to the bottom before the activation point, move the cast area further upstream.

Knowing when to strike is without doubt the hardest part of Killer Bug fishing. I have seen fisherman draw in their line and cast again blissfully unaware that several fish have taken, and then spat out, the Killer Bug. The strike is easiest when the fisherman can see the bug and fish clearly, but can also be made when just the fish is visible. It is even possible to use the line at the point where it enters the water as a strike indicator and the very best Killer Bug fishermen can be successful by striking on instinct alone.

With good light conditions and clear water it is very easy to see bugs in the water and even easier to see the fish. What could be simpler than watching the Killer Bug enter the fish’s mouth and then striking? Unfortunately fish spit out bugs very quickly and the act of striking can take a long time in comparison, particularly if the fish is a long way off or there is a lot of slack in the line. That is why Killer Bug fishing is more successful close in; it removes the need to anticipate the fish’s action. If the fish is more than 15 -20 feet away, the strike will have to start before the fish has taken the bug due to the time lag between striking and the hook being set. Fish very rarely hook themselves on a Killer Bug.

It is also relatively easy to judge when a bug has been taken by watching the fish. This is the more common technique as it is very difficult to keep watching a tiny Killer Bug as it sinks several feet away. Although you may be unable to see your bug, you should have a reasonable idea of where it is located in the river. Any fish that runs towards that rough location and then stops may well have taken. This is the time to strike. If your cast has been very accurate the fish may not have to move that far to take your bug. In this case look for a flick of the tail, a sudden move of the head or a slight upward tilt. Ironically, inaccurate casting, that causes a fish to move to your bug, is sometimes more successful as it can be easier to identify the take.

Occasionally it is not possible to see either the fish or the Killer Bug. Perhaps the river is too dirty or the light is wrong. In these conditions it pays to watch the line at the point where it enters the water. When the bug is swimming, watch for tiny, almost imperceptible checks or movement at the point where the line dips beneath the surface. If you see such an indication, strike. Occasionally the fish will take with a thump and there will be no mistaking the act, but this is rare.

Fishing on instinct alone is the most difficult of the techniques, but really it is just common sense and experience. Common sense dictates that the Killer Bug is most likely to be taken in the first few seconds of the swimming action while in the ‘shrimp zone’. Experience tells us that grayling and trout are predictable; most fishermen know the places where they are likey to feed. Combining common sense and experience leads to an instinct for where and, more importantly, when a fish is most likely to take. Striking at this point may result in success. It is certainly worth a try if it is not possible to use any of the other techniques.

No matter how you caught the first fish it is important to ‘slime’ the bug, nylon cast and leader. Fish slime has several properties which are extremely useful to the Killer Bug fisherman. Firstly the slime makes the bug taste more natural. This causes the fish to take more time in spitting out the artificial, giving valuable extra milliseconds in which to strike. Slime on the cast ‘wets’ the nylon and allows it to slip through the water more easily. This makes the bug sink quickly and force is imparted along the line with less water resistance. Finally, slime masks the distinctly human smells, such as soap or tobacco, which are left in minute traces on everything we touch.

There are no promises in fly fishing but a competent Killer Bug technique on the chalk stream is as close as one can get to a guarantee while still adhering to club rules. The technique is simple, effective, great fun and, once mastered, it is never forgotten. The Killer Bug’s biggest attraction is arguably its versatility. In today’s hectic lifestyle, with the associated pressures on valuable fishing time, and the notable decline in fly life and surface feeding, it is perhaps more relevant to modern fishermen than ever before. After more than 50 years of distinguished service the Killer Bug remains a deadly enigma, and long may it remain so.

For more great information on the thread substitutes, check out: http://EzineArticles.com/4219407

The Killer Bug was used to imitate the scud Gammarus Pulex, a fresh water shrimp, and it was often sight fished in a swimming manner by Sawyer to visible fish. The bug is alloed to wink to the bottom and made to swim in a natur methodby slowly lifting the rod tip and maintaing a tight line. The most effective place to is start the lifting of the fly a bout 1-2′ in front of the fish. Fish rarely hook themselves, so you have to be very watchful for detecting the take.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.