NAVAJO JEWELRY MAKING TECHNIQUES – INGOT

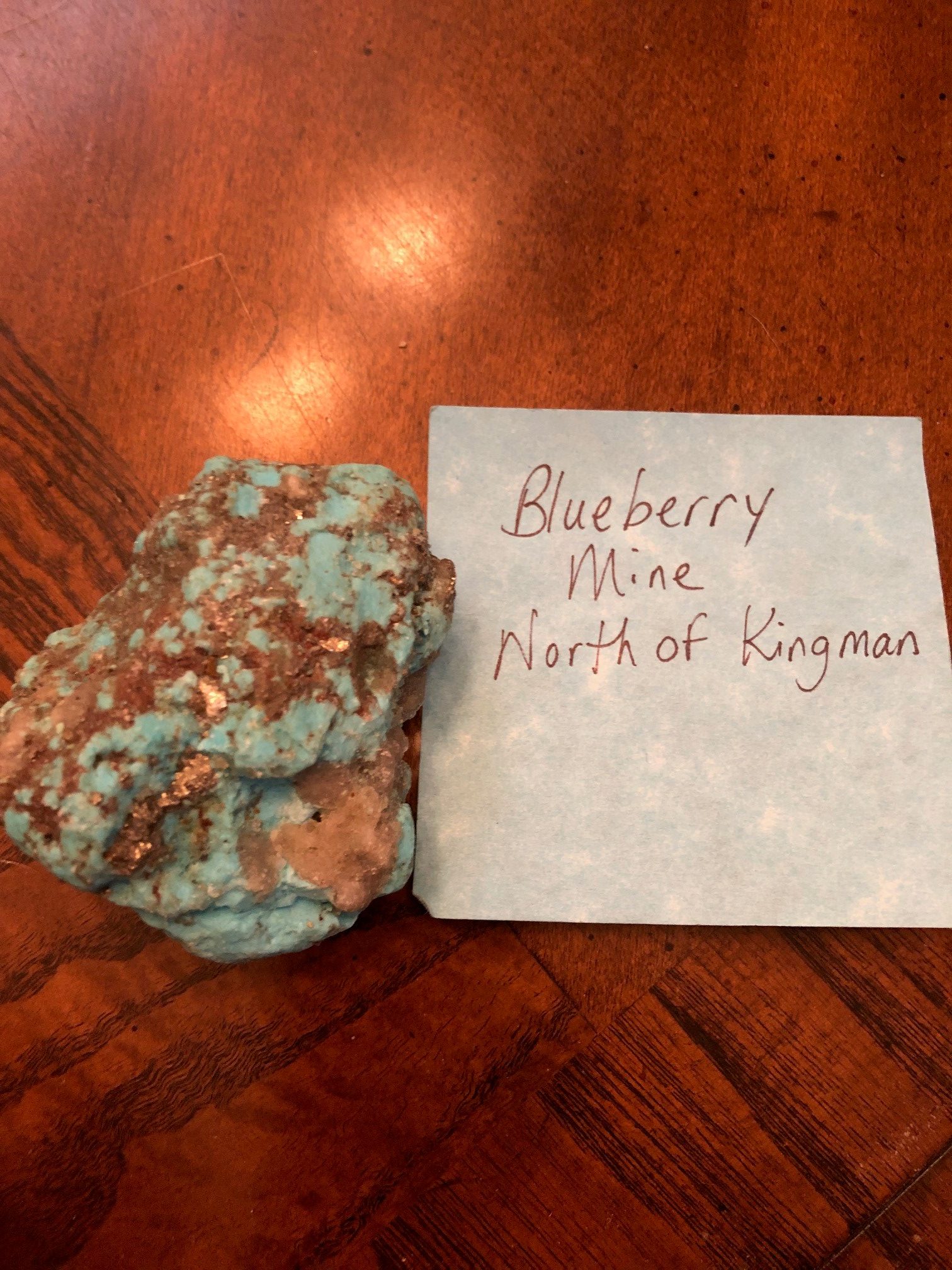

Blueberry Turquoise

From the Blueberry Mine, north of Kingman, comes an interesting turquoise that often has pyrite mixed in it. So you are saying, I never heard of the Blueberry Turquoise Mine, well, me either. Apparently it just opened earlier in 2019 and is is producing large nuggets at times.

No this isn’t Hidden Valley or Cloud Mountain or Golden Hills, the mines which are producing some the better Chinese turquoise, this is good old American Southwest turquoise.

Turquoise from mines in China accounts for about 80% of the stone on the U.S. market today, due to the scarcity of American turquoise. Only a handful of turquoise mines in the American southwest are commercially operating.

It’s great to see an American mine opening, as most of them have closed due to high operating costs compared to Chinese mines.

Cerrilos Turquoise

One of our favorite diversions is a trip to the mines to dig our own turquoise around Cerrilos.

King Manassa – Colorado Turquoise

The King’s Manassa turquoise mine, or more accurately the “King Turquoise Mine”, is located near Manassa, Colorado. It is one of the many turquoise deposits which was actively mined by Native Americans for centuries. I.P. King rediscovered the mine in 1890, and the King family has operated it ever since. It was originally called the Lick Skillet Mine.

Otteson – Royston – Thunderbird and Blackjack Mines

We are planning a trip to Toponah soon to check out some of the Royston mines featured in the Amazon Prime series, Turquoise Fever:

https://ottesonbrothersturquoise.com/mine-tours

https://www.onlyinyourstate.com/nevada/turquoise-mine-tour-nv/

Best Place to Get Navajo Pearls

https://www.silverpearlranch.com/navajo-pearls-silver-beads

___________________________________

For over a millennium, people in the Southwest have utilized turquoise for ornamental and ceremonial purposes, as well as for trading precious stones both locally and beyond the region. Turquoise symbolizes water and sky, prosperity, well-being, and safeguarding. The blue-green hue signifies creation and the desire for security and beauty. These concepts were deemed so significant that if turquoise was not accessible, its color was symbolized through alternative means.

Throughout history, individuals have endeavored to capture the essence of turquoise’s color. At times, the color held more significance than the material itself.

Wooden pendants dating back to 1200 AD were coated with green malachite paint. Anasazi pottery featured designs with parallel, diagonal lines, prompting viewers to envision blue-green shades where none existed. To enhance the stone’s blue tones, the Navajo soaked it in sheep’s tallow.

By the 1920s, the demand for turquoise surpassed its availability. To meet the needs of tourists flocking to the Southwest, Hubbell Trading Post had Venetian glass crafted to mimic the coveted stone. Native American artisans would utilize these beautifully hued faux stones when genuine turquoise was scarce.

Similarly, as ancient craftsmen painted wooden pendants to replicate the desired color, synthetic turquoise now mirrors the allure of the authentic gem at a more affordable price. If the color captures the essence, it is considered a treasure. However, discerning buyers mindful of the quality of their purchase should exercise caution.

The color of turquoise is a reflection of its surroundings. Proximity to aluminum yields turquoise-green hues, while zinc imparts a yellowish-green tint. The highest-quality turquoise, showcasing the most vibrant colors, is typically found near the surface. Exposed to sunlight and the elements, turquoise may lighten over time.

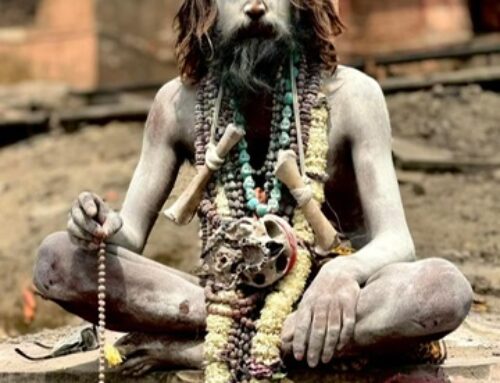

Irrespective of its color variation, turquoise carries prestige and power. Deities in Native American folklore wield weapons and reside in dwellings crafted from turquoise. The Apache believe that turquoise fills the pot at the end of the rainbow. In Zuni ceremonies, turquoise-hued face paint, masks, and body adornments symbolize Awonauilona, the life-affirming power of the sun.

The potency of turquoise is such that no horseman would ride while carrying turquoise, as it was believed to tire the horse. Hunters would draw lines with turquoise between game tracks to slow their quarry. Hung in households, turquoise was believed to ward off misfortune.

Turquoise jewelry, including bracelets, necklaces, and rings, served as portable assets; historically, Native Americans used these pieces as collateral when trading for essential goods. When they sold their produce or wool, the traders were repaid, and the jewelry was reclaimed.

It is estimated that Native Americans had been mining turquoise for approximately 1200 years before the arrival of the Spanish, with peak mining activities occurring between AD 1350 and 1600. Around 200 turquoise mines have been unearthed across the Southwest, with most believed to have been initiated by Native Americans who employed shaped stone tools to extract the precious stone from the rock.

The largest ancient turquoise mine was discovered near Cerrillos, NM, at Mount Chalchihuitl. Turquoise sourced from mines in the Cerrillos region, over 150 miles to the southeast, has been identified at Chaco Canyon.

The evolution of turquoise jewelry paralleled the era of conquest. During their 800-year rule in Spain, the Moors introduced crescent moons and pomegranate blossom motifs to Spanish culture. Spanish explorers, in search of gold and silver, rode into Native American communities adorned with crescent-adorned bridles.

The Navajo, especially, liked the symbol. They traded for it or captured it. The shape of the crescent became a naja at the base of a squash blossom necklace. Pomegranate blooms, a pattern used widely by the Spanish, inspired the squash blossoms themselves.

It is widely believed that the first recognized Native American blacksmith, Atsidi Sani, learned the craft from a Mexican blacksmith while touring “Navajo Land” with an American Indian agent in 1853. He may have added silversmithing to his skills during or after he was held prisoner at Fort Sumner, after he and his people were forced to relocate from Arizona.

Atsidi Sani and his students spread the skill. Zuni craftsmen learned the skill from Navajo teachers. Over the years, techniques and styles comingled, in lavish ways such as Navajo silver-stamped boxes decorated with Zuni inlay work.

Contemporary Artistic Expressions

Because of the work of contemporary Native art founders Charles Loloma, Kenneth Begay and others, current Native American jewelers no longer have to meet the expectations of viewers who only know Native American art as “traditional.”

Instead, they are free to merge their own inspirations with the skills and traditions they have learned throughout their lives.

Among them are Angie Reano Owen (Santo Domingo) – who, looking for a new avenue for creation amid the traffic jam of 1970s heishi, revived inlaid jewelry traditions – and Na Na Ping (Pascua Yaqui), whose elegant inlaid jewelry bears the work of a true lapidary, with stones that are meticulously cobbled together.

Both also took their paths away from tradition to reach their artistic vision. Owen merges the old (such as using wood as the backing for a bracelet) with the new (the black matrix that outlines each stone in her mosaics). Ping cuts stone with the skill taught to him by his uncles, but combines the stones in modernistic blends of color and angularity.

Like many modern Native jewelers, both are able to express their traditions in a contemporary voice.

TURQUOISE FACTS

Despite turquoise’s close identification in the US with the Southwest, other parts of the world have long held turquoise in high esteem.

Turquoise was used on the gold funeral mask of King Tutankhamen in Ancient Egypt.

-

- The oldest turquoise mines in the world, operated for thousands of years, are in Iran.

-

- The word “turquoise” comes from the French name for a beautiful blue stone they thought came from Turkey, but was actually from Persia.

-

- Turquoise is formed in arid regions by infrequent precipitation flowing through host rock and depositing minerals and salts. It is in these same regions – the US Southwest, central and northern Mexico, Andean South America, Tibet and Uzbekistan – that it is most valued as a gem stone.

-

- The Zuni word for turquoise can be translated as “sky stone.” This link between turquoise and sky is also true outside the Southwest; for example, in Tibet, the sky is sometimes called “the turquoise of Heaven.”

-

- Pueblo dancers wear turquoise regalia during the summer growing season to ensure rain.

-

- The stone’s color ranges from white (called chalk), to deep blue, pale blue, florescent yellow-green, deep green, and everything in between, but it’s the color and shape of the matrix, the veins of the host rock that run through turquoise, that contribute to its prestige and value.

-

- Turquoise is a soft stone and changes color as it is worn, becoming darker and greener. In many parts of the world it is believed that turquoise absorbs poisons and protect the wearer, or alternatively, that its color reflects the health of its wearer.

-

- Shell and turquoise are often used together. Both allude to water, one based on origin and the other on color, with the pairing intensifying the water symbolism.

- The Navajo link turquoise to protection and health. At birth, babies receive their first turquoise beads. The stone, in both whole and crushed form, is also included in puberty rites, marriage and initiation ceremonies, in healing ceremonies and other rituals. With the stone so intertwined with every stage of Navajo life, it is no coincidence that they are famed for their turquoise jewelry.