Frank Sawyer was a river keeper for The Fishing Association in Wiltshire, England. The river Avon was his home water. His grandson, Nick Sawyer, who was a special forces Captain in the Royal Services, when I met him and also moonlighted at times, offering his grandfather’s Sawyer Nymphs, has moved on to bigger and better things as Brigadier of their special forces. He was kind enough to send me some flies tied by his grandfather and the first thing that stands out, is how slim and natural they are compared to our American “pheasant tail” flies such as the Copper John. Nick wrote to me, ”Minimalism is probably a good way of describing the Sawyer approach to fishing. I spent a huge amount of money on taco that does not do the job as well as something out a fraction of the price.” before his grandmother retired she had three regular tires working for her as well and sold sawyer flies all around the World by mail. Nick Usually fist on the right hand it down to him from his father was one of the early fiber rods made in the 1960s by Hardy, the light master model. It is a fairly light rod and he like to fish with 1.5 pound cast tippet which equals American 7X. He commented that grade line on the test did not like the substitute wall as much as the Chadwick school, as perhaps it was a little bit on the purpleish side. However his father considered it a close enough match for it to work. As for the IRS to, he and his father’s consensus was that they are on the whole for faster water in the Chaulk streams In England and therefore do not sync as much as a killer bud. Clearly this is the case is they are not waited at all. He says that this would explain why the RST was attractive for the gray Lynn who are operational Cedars and will try most things but not so tempting for the trout. For a good two week holiday to the UK he suggested flying to London, staying two or three days in London and seeing the sights, visiting the theater I’m going shopping. Fly to Aberdeen and Scotland. Spent 45 days at the gleneagles versus the Highlands, go salmon fishing is at Saint Andrews go salmon fishing, and go grouse shooting if you win the lottery. Fly back to London 3 to 4 days in Salisbury go Chaulk stream fishing visit Stonehedge go pheasant shoot and visit Rural England.

his grandfather used to say, “commercial flights seem to be tied to impress the fisherman, not the fish!”

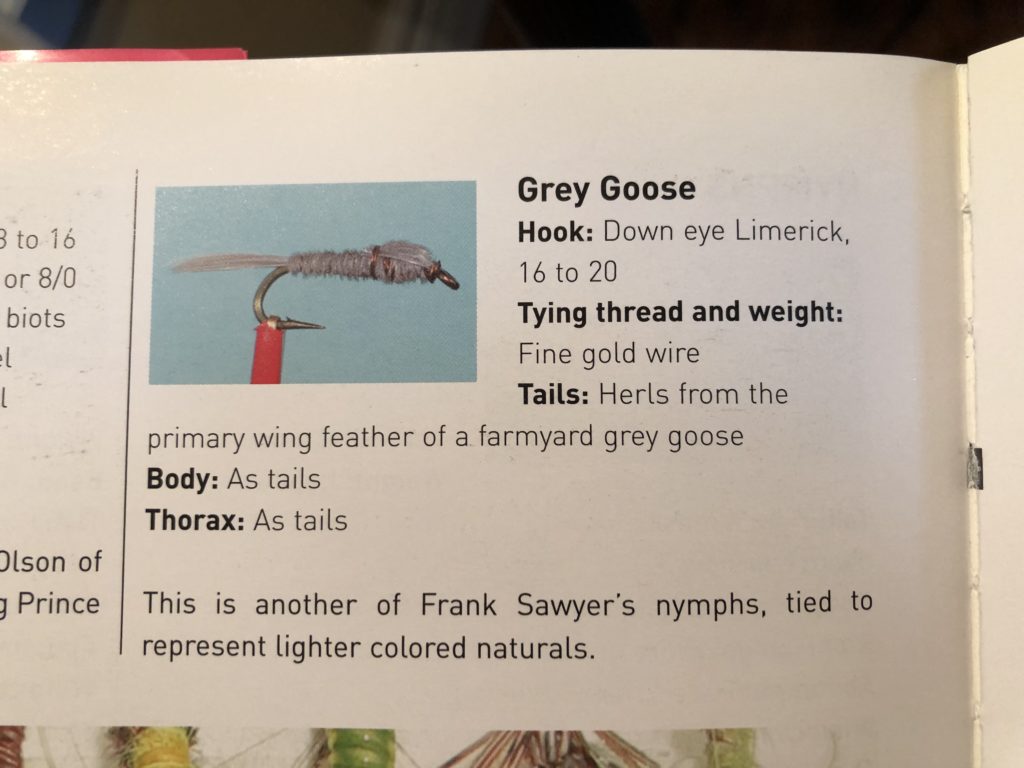

Nick writes, “The Pheasant Tail, Swedish and Grey Goose nymphs are all variations of the same pattern and fished with the same technique, often called the ‘Netheravon Style’. The Pheasant Tail Nymph is a generic darker nymph, the Swedish represents the Summer Mayfly nymph found in northern latitudes, while the Grey Goose represents the lighter coloured nymphs such as the Pale Wateries and Blue Winged Olive. From here on all three nymphs shall be referred to as sunken nymphs.”

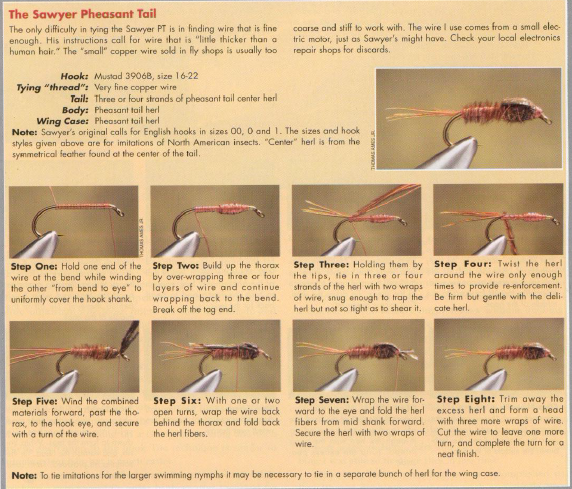

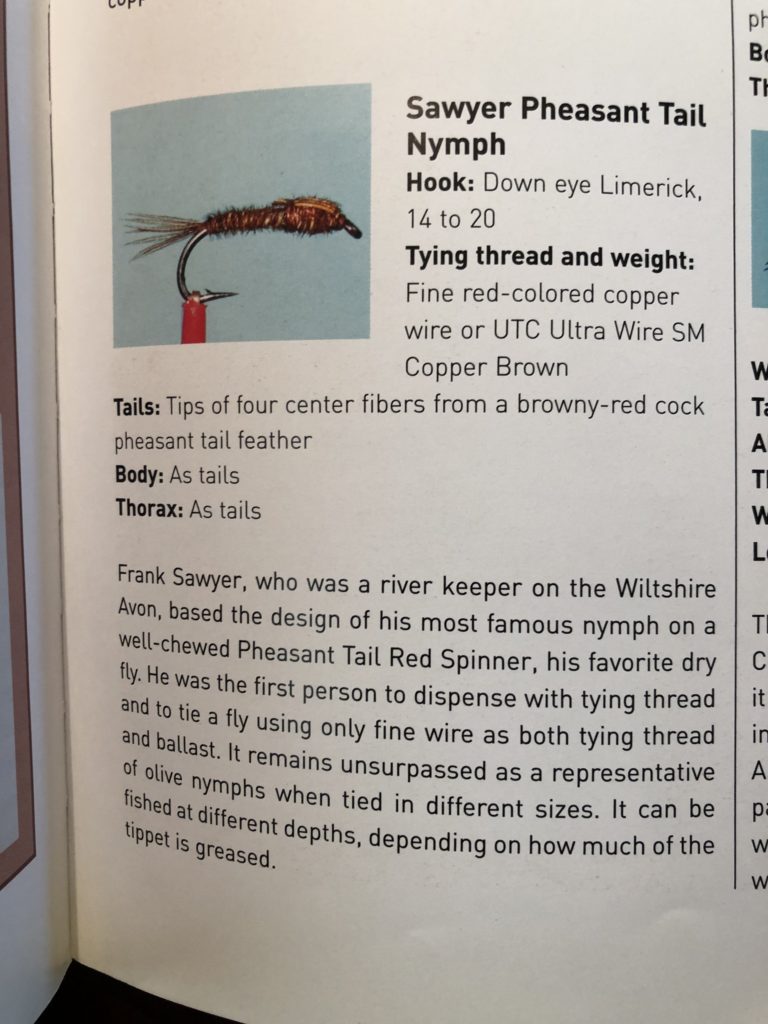

The materials needed for the fly is the proper size hook, the center tail feather from an [English] cock pheasant and thin, about .005”, dark colored relay coil wire. Frank Sawyer recommends a size 15 or 17 hook. The English anglers of that time often used odd numbered hooks [superstition probably, as odd numbers are lucky in hounds and angling and such]. Their sized 15 hook is between our size 14 and 16. Their size 17 is between our size 18 and 16. Sawyer used copper wire from a relay coil, but a copper brown Ultra wire is a good substitute. However, the copper Ultra wire is not correct, as it is too shiny in color and not reddish-brown in color. Frank Sawyer, being a professional riverkeeper, often tied them on the stream, without a vise, which is fun to try but not as easy as he makes it look.

In k Nymphs and the Trout, Sawyer states that he used only 4 pheasant tail fibers from a rooster and thin red copper wire to tie his Pheasant Tail Nymphs. He also only uses 4 grey goose herls and thin gold wire to tie his Grey Goose nymphs. When Americans use only 4 herls with the thin wires, you usually get a very slim bodied nymph, basically the body being about the thickness of the nymph hook, yet pictures in “Nymphs and the Trout” show thicker bodied nymphs. The difference is that the English pheasant tail fibers are thicker and longer, the English pheasant being larger than the American one. However, Sawyer talks about using different fiber lengths, so that the brownish-black portion of the fiber forms the wing case.

However, the actual Sawyer flies that I have from Nick Sawyer, that were tied by his late grandfather, Frank, are very thin, especially as compared to the American PT patterns by Toth and others—so don’t get the idea in your head that this is thick bodied fly, as it is not. The Killer Bug is a bit chubbier, but I have begun tying those in a slim version here in Colorado, as our caddis flies are not as chubby as those on the Avon.

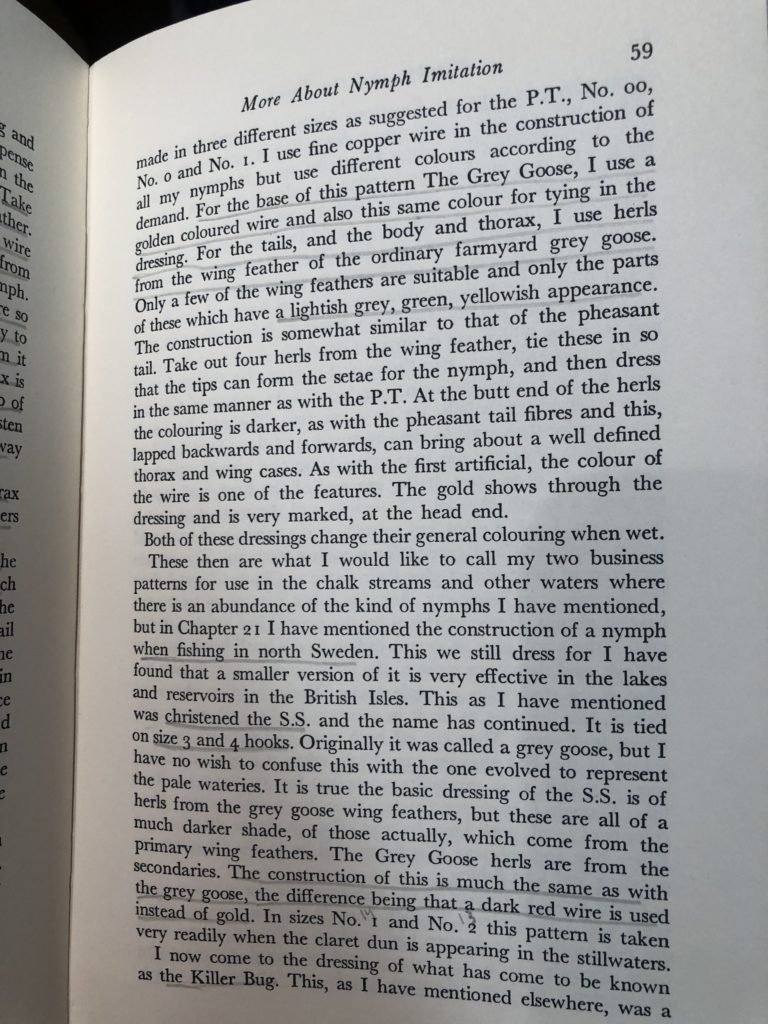

For a while Nick had a web site and some have questioned whether the nymphs are completely “true” to Frank Sawyer’s original patterns. They are, but they changed a little over Frank’s lifetime perhaps, as for instance the web site for the Grey Goose, it stated, “….fine dark coloured (enamelled) copper wire” for the body, whereas in “Nymphs and the Trout” it states on page 59: “I use a golden coloured wire.” On the web site, it stated, “Tail/abdomen/thorax/wingcase: feathers from the Canada Goose, pigeon or swan” whereas the book states: “I use herls from the wing feather of the ordinary farmyard grey goose.” Also, one of our UK-based forum members previously sent the questioner one of the current Killer Bugs and the wire color was copper, whereas, in the book, Frank Sawyer, in mentioning the Killer Bug wire states : “….colour of this not important but normally we now use red.” The truth is all of these were correct over time, as that Sawyer evolved his flies and played around slightly with available materials, as many tyers do.

From Nick Sawyer:

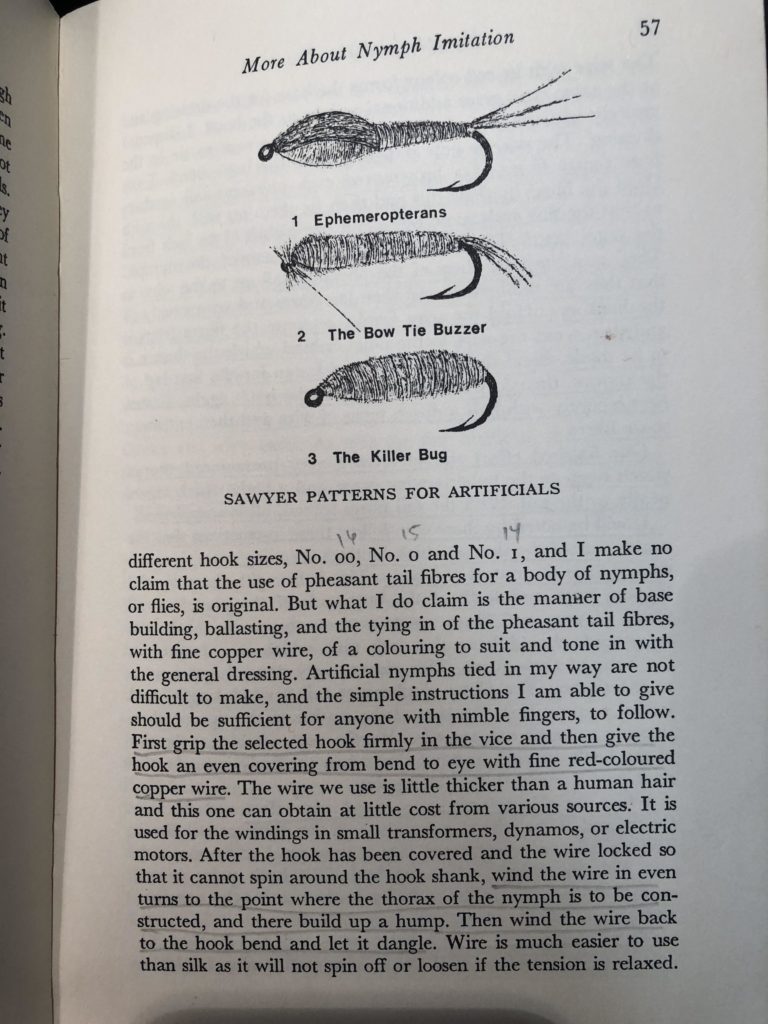

To represent the several olive patterns, the nymphs can be constructed on hook sizes 10-20. The use of pheasant tail fibres for a body of nymphs or flies is not original. But the manner of base building, ballasting, and the tying-in of the pheasant tail fibres with fine copper wire, of a colouring to suit and tone in with the general dressing, was devised in the 1930s. Artificial nymphs tied using this method are not difficult to make, and the simple instructions I am able to give should be sufficient for anyone with nimble fingers to follow.

First grip the selected hook firmly in the vice and then give the hook an even covering from bend to eye with fine red-coloured copper wire. The wire we use is little thicker than a human hair and this one can obtain at little cost from various sources. It is used in the windings in small transformers, dynamos, or electric motors. After the hook has been covered and the wire locked so that it cannot spin round the hook shank, wind the wire in even turns to the point where the thorax of the nymph is to be constructed, and there build up a hump. Then wind the wire back to the hook bend and let it dangle. Wire is much easier to use than silk as it will not spin off or loosen if the tension is relaxed.

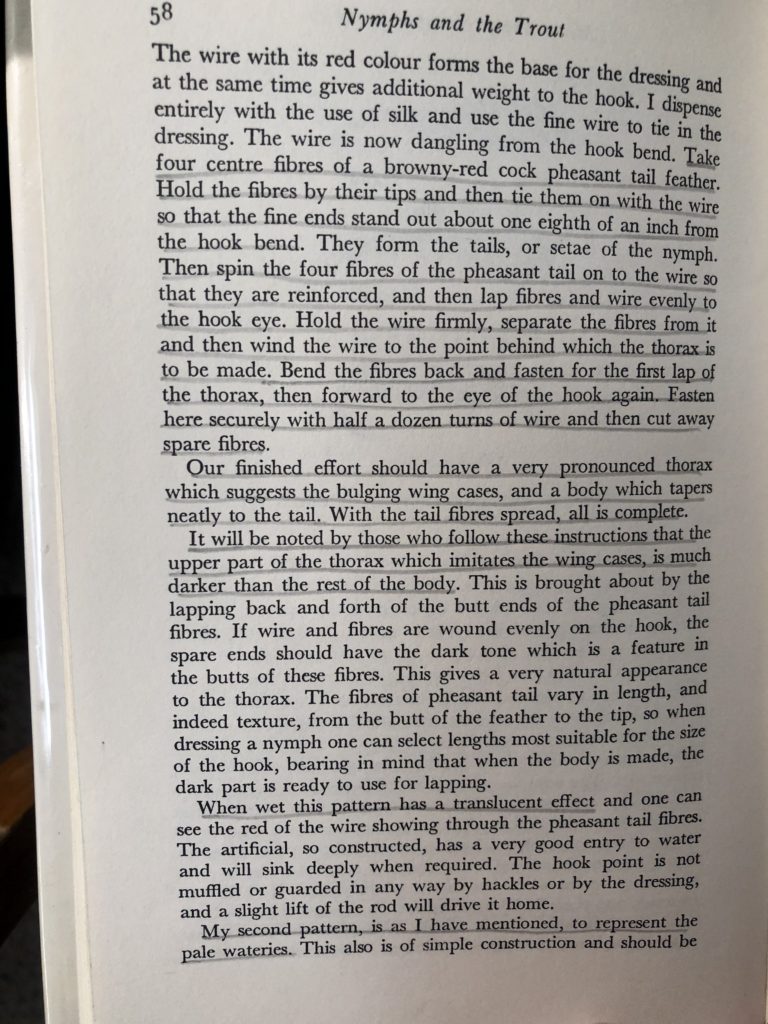

The wire with its red colour forms the base for the dressing and at the same time gives additional weight to the hook. I dispense entirely with the use of silk and use the fine wire to tie in the dressing. The wire is now dangling from the hook bend. Take four centre fibres from a browny-red cock pheasant tail feather. Hold the fibres by their tips and then tie them on with the wire so that the fine ends stand out about one eighth of an inch from the hook bend. They form the tails or setae of the nymph. Then spin the four fibres of the pheasant tail on to the wire so that they are reinforced, and then lap fibres and wire evenly to the hook eye. Hold the wire firmly, separate the fibres from it and then wind the wire to the point behind which the thorax is to be made. Bend the fibres back and fasten for the first lap of the thorax, then forward to the hook eye again. Fasten here securely with half a dozen turns of wire and then cut away spare fibres. Our finished effort should have a very pronounced thorax which suggests the bulging wing cases, and a body which tapers neatly to the tail. With the tail fibres spread, all is complete.

It will be noted by those who follow these instructions that the upper part of the thorax which imitates the wing cases, is much darker than the rest of the body. This is brought about by the lapping back and forth of the butt ends of the pheasant tail fibres. If wire and fibres are wound evenly on the hook, the spare ends should have the dark tone which is a feature of these fibres. This gives a very natural appearance to the thorax. The fibres of pheasant tail vary in length, and indeed texture, from the butt of the feather to the tip, so when dressing a nymph one can select lengths most suitable for the size of the hook, bearing in mind that when the body is made, the dark part is ready to use for lapping.

When wet, this pattern has a translucent effect and one can see the red of the wire showing through the pheasant tail fibres. The artificial, so constructed, has a very good entry to water and will sink deeply when required. The hook point is not muffled or guarded in any way by hackles or by the dressing, and a slight lift of the rod will drive it home.

Article Source: http://EzineArticles.com/4220559

The sunken nymph pattern is generic and not intended to represent one particular species. The inventor of the Pheasant Tail Nymph, observed that swimming nymphs tuck in their legs and appendages and so he dispensed with these when he designed the artificial. It is this simplicity which makes sunken nymphs so deadly – it matches virtually all swimming nymphs found in the world today. This is why it has pride of place in my fishing equipment.

The Netheravon Style of nymph fishing requires quick reactions and a knowledge of what is going on under the water. The take is very subtle and is easily missed if the fly fisher does not anticipate what will happen. If one can see the nymph in the water then things are a little easier but this is rare unless one is lucky enough to fish clear chalk streams and rivers. It is more common to see the fish and even more common to see the leader – both are useful indicators.

Obviously if one can see the nymph and the fish it is simply a case of striking when the nymph disappears inside the mouth of the fish. This requires good eyesight as well as clear water. The fish itself is a useful indicator even if one can’t see the nymph. If the fish makes a run and stops then it is likely to have taken a nymph. If it stops in the rough area of where you think your nymph is located then strike. If all that can be seen is the leader, then the trick is to watch for small twitches at the point where the tippet disappears into the water. This can indicate that a fish has taken the nymph.

Regardless of which method of indication is used, one must always bear in mind that the fish will only keep the nymph in its mouth for a fraction of a second before it spits it out. Fish will rarely hook themselves so there is only a very small window of opportunity to strike. Once you have caught the first fish of the day, rub some fish slime on the nymph. This makes it taste more natural and the fish will not be quite so quick to spit it out.

Article Source: http://EzineArticles.com/4220526