I was recently given a silk line line, which I am going to try out on the three bamboo rods which were gifted to me by Rim Chung and Gary Dewey. Ever since 2013 when Scientific Anglers was purchased from 3M by the Orvis Company, based in Manchester, Vermont, the first ownership change for Scientific Anglers in decades, their lines have gone downhills and Rio and others have come up. This sale lead to a complete rebranding of the company, with a new color scheme, new logo, and new packaging. Sometimes, in faces of change, we need to return to the old, as well as trying some of the new. Silk fly lines are one of the originals behind horse hair lines.

It’s extremely difficult, if not impossible, to tie your leader to the line with a nail knot or similar connection, since the tip of the silk line is much finer and more flexible than the butt of your leader. So, superglue is often applied to assist in the holding of the knot.

On the other hand, I have discovered that I can turn over even very long leaders using leaders with a butt diameter of only .015 or even .013. Many old fly fishing books have illustrations that contain directions for attaching leaders to silk lines. I have found that a tiny loop spliced in the end of the line, and a perfection loop in the butt section of the leader is the perfect solution. This is not only convenient for attaching leaders, but for reversing the line on the reel.

Cleaning and dressing a silk line is not the onerous burden modern line makers would have you believe. Examining any line imperfections before fishing is sound practice. Before stringing your rod, use your fingers and a felt pad floatant to test the line. (Mucilin in a red tin, for nostalgia’s sake!). The entire procedure takes about three minutes. After fishing, strip the line and clean it with a dry rag before storing it back on the reel.

At the end of the season, wash the line in soapy water and store it, undressed, in loose coils in a shoe box. The varnishes and dryers employed in the manufacture of the Phoenix line are more chemically stable than the more volatile hydrocarbons used in modern lines. They will not get tacky if properly handled.

The greatest drawback to a silk line is the price. However, for those who love to tease trout in spring creeks with small flies, fine tippets, bamboo rods and vintage reels, there is something immensely satisfying about marrying a fine piece of cane with traditional silk line. They were made for each other.

A bamboo rod feels slightly sluggish with a modern line. Even a modern graphite rod will perform better with the proper weight silk line. The added bulk of the plastic coating increases friction in the guides and adds wind resistance to the cast. If you really want to explore the capabilities the maker built into your fine cane rods, you owe it to yourself to try a silk line. Oh yes, and then there’s the smell!

I have adapted a lot of my comments below from an article, Re-Discovering Silk, by Reed F. Curry.

My search for thinner, suppler, better flylines began the day I discovered that the line/leader loop of an expensive DT6F line wouldn’t fit through the last few diminutive snakes of a new-to-me ’30’s vintage cane rod. To be honest, there was another spur to the search, the simple realization that, if cane had properties more modern materials lacked, it was probable that other excellent fishing tools had been left behind in the relatively recent wash of technology.

The result of my research was a return to a material carried from the same land as the cane itself – Silk. Since I tried my first silk line some years ago, I’ve learned the relaxing rhythm of a 100 year old wet fly rod that had been merely a sullen stick with a modern plastic line draped on it; I’ve come to delight in the new sight and sounds of casting, the translucent honey-colored line cutting the wind, the gentle laydown of the silk line’s delicate tip onto the surface film; and I’ve shared the pleasure as a friend’s new cane creation suddenly came alive in his hand, casting more line, with less effort, than ever before. Does this all sound just a little incredible? After all, it’s only a fly line. . .

The evolution of fly lines determined, to a large degree, the shifting design characteristics of fly rods. This was evident as early as the 1890’s when oiled silk replaced horsehair-and-linen lines and the miniscule flip-ring guides were replaced with the modern snake guides. For, with snake guides came the ability to “shoot” line; and with oiled silk came the opportunity to float a dressed line, opening the way to the use of the dry fly. That was his intent when Frederic Halford, the “Father of the Dry Fly” developed and patented the first solid woven tapered silk fly lines. But this new Dry Fly fishing in turn required a slightly faster rod to handle the false casting necessary to drying the early, soft-hackled flies.

Silk was the premium line during the early years of dry fly fishing and the “Golden Age” of rodmaking; and it met all the requirements of the day. But with the end of the Second World War the new miracle, “Nylon,” was marketed as a possible substitute for silk. It had proved satisfactory in parachutes and stockings, why not flylines? Initially, the Nylon line was oiled and honed like its silk counterpart, and required much the same care. Enter the 1950’s, the age of Science for Convenience, Inventions liberating the Common Man (and Woman) from the drudgery of maintenance and care; Automatic Washers, Self-Cleaning Ovens – and plastic, no-maintenance flylines. The man just returned from war and building a family had little time to spend at streamside, so the appeal of anything that optimized his fishing hours was great. However, it was a mixed blessing, for the advent of synthetic flylines, comprised of a uniform hollow nylon core covered with a tapered Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC) finish, triggered a rapid and serious degradation in fly rod taper and action. The reason for this may be found, principally, in the word “Diameter.”

Size Does Matter

The increase in diameter of flylines began innocuously enough. The early oiled-Nylon line was as much as 40% lighter than the silk, not an advantage for casting, and quite confusing to the anglers who bought their lines by the diameter, not the weight.

The new line floated admirably (except the tip), but this buoyancy was produced by reducing the specific gravity, and increasing the volume of the line. The old method of using diameters to determine the line for your rod became impractical; the difference in specific gravity between the old silk and the new PVC, and even between one plastic line and another, was too great. In order to provide a meaningful method for determining the line load for a given rod, a new system was developed which referred to the weight of the line rather than the diameter. Diameters were thus free to expand… and they did. In order to float the tips, which had the same size core as the belly, the delicate .020″ (“I”) tips of the oiled Silk line gave way to .035″ or greater for the PVC line. To drive these lines through the air required a stiffer rod, larger guides, and a much different method of casting. The reason for this is obvious, the larger diameter lines had tremendous air resistance that could only be overcome by more energy from the caster. The days of relaxed casting with subtle wrist action yielded to the “high linespeed” arm waving school, as anglers struggled to make the ever more bloated PVC lines load the rod.

Line Types

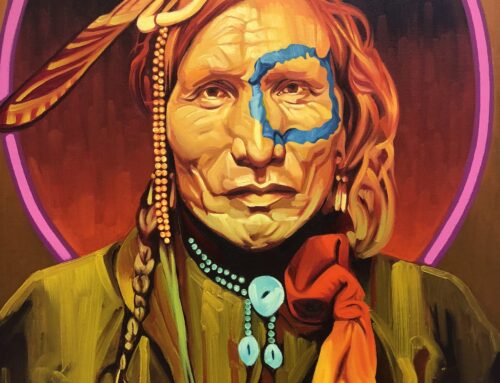

Silk lines in all colors and the Mucilin to dress them.

To those persons familiar with them, a “Silk fly line” refers to a braided, oiled, silk line, usually vacuum-dressed and hand-honed (rubbed carefully with fine abrasives to level the oil/varnish coating). This should not be confused with the hard “enameled” silk lines that were popular for a time late in the 19th century. The enameled lines wore quickly, seldom lasting more than one season, whereas a well-constructed oiled silk line can endure decades of use. Within the realm of oiled silk there exist different braiding patterns, producing what are known as “hard”, “medium”, and “soft braid”. The hard will shoot and wear better, but the soft will be more supple and forgiving when striking large fish. The early writers recommended the hard braid for most trout sizes (up to “C”) and the medium or soft braid for the larger sizes. Of far greater importance, of course, is the taper of the line itself. Silk lines have been made in as many, or more, varied and sophisticated tapers than modern plastic lines. The subject of line tapers and creating your own unique tapers, is beyond the scope of this article, but fascinating, nonetheless.

The Wind

The thinner diameter of the silk line is immediately noticeable as you line it on your rod for the first time. If your rod took a PVC DT5F and you use a DT5 silk you will be surprised at the difference as you start false casting; you might even need to go down to a DT4 because the decreased air resistance makes loading so much easier. The front taper has more weight and starts to load the rod almost immediately. As more line is worked out, you’ll notice that less effort is required to sustain it in the air. And if a wind comes up, you’ll be able to cut through it with greater effect than ever before. Now start shooting the line. The noise may be a bit disconcerting at first; the rustling, hiss as the braid murmurs through the guides. The shoot, however, will make you soon forget that.

Of course, perception of the ease of casting is highly subjective. So, in order to get an unbiased view of this aspect of silk lines, I took a trip to Hunter’s Angling Supplies in New Boston, New Hampshire (www.huntersangling.com). Nick Wilder, the genial owner, was gracious enough to choose five graphite rods from stock (three Sage, a Winston, and a Loomis) and send me to the river with one of his people, Capt. Greg Nault. Greg, it turns out, is not only a superb caster but he had never used a silk line before. We tried both Phoenix DT in 3wt and 5wt and Thebault WF in 3wt and 5wt. Greg observed that the line “doesn’t stretch, it seems to transfer power better”, “loads nicely and shoots beautifully”, “seems to float higher than other lines, has an easy pickup and rollcasts well”, “it’s very limp and lays very straight” and “doesn’t get swamped in rough water”.

In short, he was quickly wearing a delighted grin and inquiring about the cost of a line, though he confessed to me afterwards that he had been quite skeptical at first.

A silk line has virtually no stretch, which makes for both very positive hook sets and better control in casting. You’ll probably quickly notice that your silk line is suppler than plastic and has less tendency to memory — no more of those annoying coils that grab at your reel handle, or the need for stretching the line before use, as is recommended for some PVC lines. This is because the PVC line is essentially a semi-rigid pipe (in larger sizes it’s the plumbing for your bathroom sink). The silk, on the other hand, is a thin rope. Think about it.

One of the more curious developments of recent years has been the braided leader. This was created, I assume, because the thick, stiff tip of the plastic line has a tendency to slap down into the water; especially because of the need to generate a high line speed in order to get full extension of the light PVC line. The braided leader emulates the tapered end of a silk fly line. With the terminal end of an “IEI” miking at .020″ it is thinner than some monofilament leader butts, and it has the smooth laydown that the braided leaders were designed to deliver.

The next discovery you’ll make will occur when the silk line lands gently on the water. . .it floats higher than your plastic line.

Approaches to Floatation

The specific gravity of a PVC line is less than 1.0; silk lines run 1.2 – 1.4. Yet, the silk floats well. This is possible because the lines use different approaches to floatation. Most modern PVC floating fly lines achieve buoyancy entirely through displacement. Archimede’s Principle at work, the line must displace a sufficient volume of water to compensate for its weight; and to do this it must settle deeply into the water. The silk line relies upon the same principle as the floating artificial fly … surface tension. The dressing applied to the line repels the water (it is “hydrophobic”, but not rabid), floating the line high in the surface film. Thus, the silk line is smoother in its lift from the water, and creates less surface disturbance in drawing it back. This is especially evident in the ease of rollcasting.

Of note, a number of PVC lines, the SA Ultra 3, the Airflo Polyfuse 7000, and the Orvis Silver Label Hy-Flote Extra, advertise the use of a hydrophobic coating as well as microballoons to achieve floatation. This may well be the answer to the belief that the tips of most plastic lines float rather poorly. The specific gravity of the PVC line increases as the volume of the microballoons decreases, while the core diameter remains constant. Obviously, with less volume to keep it afloat, the tip of the plastic line did not float as well as the belly.

. . .And Now, the Downside

Well, there is the cost of silk lines. I’ve found only two manufacturers in France — Phoenix and Thebault – and one in Italy – Terenzio. In comparing them, there are several marked differences. The Thebault lines appear to be translucent, indicating saturation with an oil, such as was common to old silk lines; whereas the Phoenix has greater opacity, a waxy look. In color both might be considered a shade of pale gold, the Thebault only slightly darker; but the Thebault has a slight mottling indicative of some hand work, the Phoenix is completely even in tone.

The tips of both the Thebault and Phoenix, in light line weights, are .024″, certainly a lot more delicate than PVC lines. The Thebault line comes with several ounces of a proprietary dressing in a tin container (several seasons worth), the Phoenix comes with a “tin”(plastic) of the red Mucilin (good for half a season).

The Thebault will require some breaking in to work the initial stiffness out, not so the Phoenix. The Phoenix appears to be a more polished product overall, but at a higher price. A new DT4 made by Phoenix runs $250 regardless of the U.S. distributor… and delivery can be a problem, Phoenix only produces 600 lines a year. Thebault has more modest prices, a far greater production capacity, and a more extensive range of lines, offering 1/2 double tapers, as well as DT and Spey. You should be able to get a 1/2 DT Thebault from an U.S. distributor for $118.

I have not been able to use a Terenzio for comparison purposes, but they receive good reviews.

*** Sidebar *** Both Phoenix and Thebault lines are available in the U.S. from Olaf Borge Mail: P.O. Box 361 Viroqua, Wisconsin 54665 Email: oborge@mwt.net Phone: 608-675-3509 Fax: 608-675-3681 url_ www.silkflylines.com

Terenzio lines may be purchased from A. B. Herndon Rod Co. PO Box 275 50 Blue Place Road Malo, WA 99150 Phone 509-779-4247 Email: info@herndonrods.com url: www.herndonrods.com

*** end sidebar ***

Costs of silk lines should be considered in terms of their useful life. A silk line, with care, will last 20 years, though I have some that are far older. In 20 years I would go through 10 PVC lines (let’s see, 10 * $45 = $450), yes, I can rationalize the higher initial cost of silk.

The price of silk lines is easily understood when you consider their manufacture. The line is first braided from as many as 16 silk threads. The machine must be constantly monitored for thread breakage, and threads added or subtracted at the proper moment to create the complex taper of the line. After the raw line is complete, it is placed in a warm bath of a proprietary mixture of oil (e.g., Tung oil) and varnish, and a vacuum is drawn to remove air from the braid, thus permitting maximum penetration of the oil. The line is then removed and dried over a period of some days before the coating process is repeated. Once a buildup of varnish is on the line, the line is hand polished between coating steps. It can take many man-hours, over several months, to produce a silk line of the quality of a Phoenix.

Strength is another factor to consider in using a silk line, though this is not generally of much concern. Our grandfathers were able to land 40 pound Atlantic salmon on their silk lines. . .but they were using relatively fragile gut leaders. Unlike gut, the modern tippet material is of both fine diameter and high tensile strength. This could easily permit you to use a tippet that was stronger than your line. The breaking strength of an HEH silk, dry, is from 14-18 pounds; when wet, the same line would actually test a few pounds higher for sudden stress. This, of course, is adequate for most situations. If, however, you insist on fishing with a tippet testing more than 12 pounds, don’t use silk. Salmon lines would usually be GAF or larger, and these test out at greater than 20 pounds; but, again, the tippet used should be 12# or less.

Buying tapered leaders to match your silk lines may be difficult. With the terminal end of an “IEI” gauged at .020″ it is thinner than some monofilament leader butts. I build my own leaders and start them with a butt of .015″ Maxima for 5wt and above, and .013″ Maxima for 3-4wts. Anything thicker than this makes for a poor transition from line to leader.

—- Care and Feeding of Your Silk Line

A little preventive care, such as we give anything we value, will ensure a supple, pleasurable line for years to come. A silk line must be dressed with a floatant before starting the day streamside. The subject of line dressings used to be good for an hour’s argument at fishing lodges anywhere in North America — deer fat vs. bear fat, turps vs. mineral oil, etc. I eschew all the home recipes, especially the animal fats which cause oxidation of varnish and tackiness. I stick tenaciously with Red Tin Mucilin; never the Green Tin, it contains Silicone which is difficult to remove from a cane rod and causes blemishes when re-varnishing. Perhaps, its just part of the tradition; or childhood memories of struggling to open that red tin with wet hands and watching the cover go spinning off into deep water. Someday, I’ll try some experimentation with non-traditional floatants; for example, I’ve used Albolene, but found it too greasy, and I may try Sno-Seal, since it’s wax-based.

How you apply the mucilin is a matter of preference. Some use their fingers; I prefer to use the felt pad that comes with the mucilin. Always remove any excess, you only need a very thin coating. You can buy gadgets to perform even this task; and fishermen love their gadgets. But the best, most versatile implements you might carry are a bandana to remove excess mucilin, and an 8″ square of chamois to dry your line (and flies). You would want to pull the line through the chamois during fishing if the line starts to sink – this will give you another half hour of casting before you retire that end of the line for the day.

An antique Line Dryer that can strip off 30 yards of line in a minute. You’ll find that it is handy to have loops, for line to leader connection, on both ends of a DT, and a large enough loop in the backing line to permit you to pass the reel through. Over the course of a days fishing, perhaps within four hours, an oiled silk line, like an oiled dry fly, will have absorbed sufficient water to cause it to sink. At this point you ave a number of options. If you have a concept of flyfishing as the “Contemplative Sport” you might unspool your line onto the bushes at streamside, boil a pot of tea, and have a pleasant lunch while waiting for the afternoon hatch. Of course, (if you’re using a double taper) you might just switch the line end for end; dropping the reel through that large backing loop and rush furiously back to the water. Whichever approach you take, before you drive home, strip the line in loose coils onto the back seat of the car. In most climates it will dry overnight. If you fish more than one line in the course of a day or keep a dog in the backseat of your car, you may want to get a Line Drier. Ultraviolet light does not have a deleterious effect upon silk lines, as it does with PVC. The enemy of silk is mold. Keep your lines dry when not in use. An invisible fungal attack (read “rot”), from leaving the line stored wet, may reduce the breaking strength of any silk line to just a few pounds.

Change is a constant. But sometimes looking back at what we left behind may serve us well. Try a silk on that favorite rod, you won’t regret it.

_______________________

A Note on Bamboo Fly Rods

Generally speaking, the shorter the rod, the more desirable it is for fishing and the higher its value. Fly rods 8 feet or shorter usually command the highest dollar. Condition is so important! Don’t buy into the myth that just because a rod was made by a well- known shop or individual, it is a better-quality rod and worth more. For example, Leonard rods varied widely in quality, depending on who owned and managed the company after the fire that gutted the H. L. Leonard Rod Company in the mid-1960s. The exception to this rule is Payne rods made by either Jim Payne or his father, Ed Payne. They held to the highest-quality standards of any rod maker for more than sixty years. And legendary bamboo fly fishing author who is dyed in the tweed, John Gierach, considered those 7 1/2 footers made by Jim Payne to be the best, so much so that he thought they were out of reach for even him. As of 2023, they currently go for $2000-6000. Gierach writes, “In many cases, aficionados can trace an apostolic succession from one shop to the next as apprentices left to start their own companies. Think of Hiram Leonard, who began producing split-bamboo rods shortly after the Civil War. He taught Edward Payne, who then opened his own business, E.F. Payne Rod Co., where he passed on the craft to his son Jim, who then took over and continued to build bamboo rods until 1968. The lineage of others, such as F.E. Thomas, Goodwin Granger, Pinky Gillum, and Everett Garrison, can be followed in a similar way.” Gierach writes a lot of his friend Mike Clark of Lyons Colorado, as well as other rod builders such as Bradord and Vince Zounek 303-823-6721. He owns 7 1/2 footers made by Bradford, Leonard, F.E. Thomas, and Granger. 7 foot 9-inchers by Mike Clark (whose shop also sells Archie A.K. Best’s flies, and a rod from Walter Babb. And 8-foot 4-weigts by Thomas and Charlie Jenkins. He says they all share the quick, tippy dry-fly action that’s characteristic of the Golden Age of bamboo rods.

Gierach says, “But it was our generation that took nymphing from something a respectable fly fisherman just didn’t do, to something a respectable fly fisherman didn’t do in front of witnesses, to a minor tactic that was good for a few extra trout between rises, to a method so effective that some saw no reason to fish any other way.” But then again Gierach is a self admitted hippie who “believed in peace, love and the simple life in a general way, and still do, but my redneck streak (from Minnesota?) ran deep and the yin-and-yang symbol you saw everywhere then as an emblem of balance and harmony always reminded me of two pork chops in a frying pan.”

Here are some good ones:

High-end rods: Paynes (made by Jim before his death in 1968), Gillums, Garrisons, Dickersons, “Sam” Carlsons, Paul Youngs.

Midlevel rods: F. E. Thomases, H. L. Leonards (shorter than 8 feet), E. C. Powells (hollow built), R. L. Winstons (shorter, San Francisco made).

Lower-level rods: Heddons, Grangers, Phillipsons, Montagues, South Bends, Shakespeares . . . and many more.

A few of mine:

- Phillipson Premium 8’ 4 ¼ HDH, 3-piece, with metal seat, it’s 2011 value is $550 from Gary Dewey bamboo fly rod

- Winston Powell, 7’6”, with 2 tips, with metal seat, made by Glenn Brackett for Rim Chung, 2011 value $2700 bamboo fly rod

- Duracane 7 ½ foot, serial 1706, with cherry wood seat, made for Rim Chung, 2011 value $2200 bamboo fly rod

- French bamboo fly rod made by Pezon et Michel, model speciale normale 8.5′ in wf5