I just read an article entitled “It’s All About the Bit That Works Best For You.” I couldn’t disagree more, it’s all about the bit that works best for your horse. Like all things American, we have gone crazy for the latest gadget when it comes to bits. Wilson Dennehy and Marvin Beeman only used two bits, a snaffle or a pelham, for show jumping, hunting and polo. Why? Because “I never found a horse that wouldn’t go well in one or the other,” they both independently said to me.

As for the Snaffle, there are a few kinds worth mentioning.

First, the Eggbutt Snaffle:

The Eggbutt is a very common multi-discipline style of cheek piece for snaffle bits. The eggbutt snaffle minimizes two problems that can arise with its cousin, the loose ring snaffle, whose rings can pinch the edges of the horse’s mouth, and which doesn’t provide much lateral stabilization. By flaring out the ends of the mouthpiece and joining the rings with flush swivel joints above and below where the lips contact the edge of the bit, the eggbutt can be a more comfortable alternative for many horses. The edges of the mouthpiece are less likely to pinch the horse’s lips, and because the cheek is fixed in relation to the mouthpiece, the bit offers moderate lateral control.

When the bit is pulled laterally through the mouth, there is some resistance on the opposite side, which can help encourage the horse to turn with less danger of pulling the bit through the mouth than exists with a loose ring snaffle, though more than with a dee-ring or full cheek snaffle.

By having rings fixed to the mouthpiece, the eggbutt does give up some mobility, in that the position of the mouthpiece is more influenced by the movement and position of the cheek pieces than by the movement of the horse’s mouth, unlike the case with a loose ring snaffle.

Second, the Full Cheek Snaffle:

Used especially for horses that are tough to steer and turn, the Full Cheek is the most extreme type of corrective cheek piece that can commonly be found on a snaffle. With a small ring fixed to the mouthpiece on a swivel joint, and two arms extending above and below the mouthpiece, the main purpose of this bit is to exert lateral pressure on the horse’s mouth. When one side of the bit is pulled, as in turning, the opposite side presses against a broad section of the lips and cheeks. This can be particularly useful with horses that are having difficulty learning to respond properly to direct rein pressure, and can sometimes help correct horses who tip their heads trying to evade direct rein pressure. One of the biggest dangers with full cheek snaffles is that posed by the lengthy arms. Getting hooked on something can cause terrible harm, even to the horse’s nostrils as well as the horse’s mouth.

Third, and our favorite, the Dee Ring Snaffle Bit:

The Dee Ring Snaffle Bit is a compromise between an eggbutt and a full cheek snaffle. It has vertical shanks that extend above and below the mouthpiece, and these are joined on the top and bottom by a D-shaped ring on swivel joints. Like the eggbutt, it helps prevent pinching at the corners of the mouth, though generally without as much bulk as an eggbutt, and it provides fairly substantial lateral control through the vertical shanks, though without the dangers posed by the arms on a full cheek snaffle. Because of this combination of control and safety, the dee ring snaffle has been popular in horse racing and jumping disciplines.

Finally, the simpliest, Loose Ring Snaffle Bit:

The Loose Ring Snaffle is one of the most common types of snaffle cheeks, and generally considered to be the best style of cheek for disciplines requiring sensitive contact through the reins, such as dressage. Because the ring-shaped cheek pieces are attached to the bit by running through holes bored into the ends of the mouthpiece, the mouthpiece to move freely in relation to the rings. This allows the mouthpiece to move more independently with the tongue and jaw movements of the horse, even when the reins are maintaining pressure on the bit. This is generally considered an advantage in disciplines like dressage in that it encourages a relaxed jaw and mobile tongue, but some horses can find this freedom overly stimulating and get too playful with the bit, especially when there is no rein contact helping to stabilize the bit. The rings are also able to swivel freely in a lateral direction, allowing for clear transmission of direct rein aids, which is particularly useful with young horses. Most cheeks used in snaffle bits are able to swivel laterally, but as the name suggests, the loose ring has the least resistance in this respect.

And, then we turn to the bit that provides more control and braking power than the Snaffle, the Pelham:

A pelham bit combines elements of both a snaffle and a curb bit into one mouthpiece. “Snaffle reins” attach to rings on the side of the mouthpiece, while “curb reins” attach to shanks designed to apply pressure to the poll and under the chin via a strap or chain. A pelham encourages the horse to bend at the poll, without the bulk and difficulty of two separate mouthpieces. A pelham is a leverage bit, meaning that is increases the force but reduces the extent of movement applied by the rider. Unlike a snaffle bit, the curb rein can amplify the rein pressure several times over, depending on the geometry and length of the shank. Shank lengths are 2 inches (“Tom Thumb”) and longer, although most are less than 4-5 inches. The relation of the purchase arm—the length from the mouthpiece to the cheekpiece rings—and the “shank” or lever arm—the length from the mouthpiece to the lowest rein ring, is important in the severity of the bit. A long lower shank in relation to the upper shank increases the leverage, and thus the pressure, on the curb groove and the bars of the mouth. A long upper shank in relation to the lower shank increases the pressure on the poll, but does not apply as much pressure on the bars of the mouth. However, longer-shanked bits must rotate back further before applying pressure on the horse’s mouth than shorter-shanked bits. Therefore, the horse has more warning in a long-shanked bit, allowing it to respond before any significant pressure is applied to its mouth, than it would in a shorter-shanked bit. In this way, a longer shank can allow better communication between horse and rider, without increasing severity. This is also directly dependent on the tightness of the curb chain.

If the bit has a 1.5″ cheek and a 4.5″ lower shank, thus producing a 1:3 ratio of cheek to lower shank, while the ratio of the cheek to (upper + lower) shank is 1:4, and producing 4 pounds-force of pressure on the horse’s mouth for every 1 pound-force (4 newtons per newton) placed on the reins. If the bit had 2″ cheeks and 8″ shank (ratio of 1:4), the bit will produce 5 lbf (22 N) of tension for every one applied by the reins (5 N/N). Regardless of the ratio, the longer the shank, the less force is needed on the reins to provide a given amount of pressure on the mouth. So, if one were to apply 1 lbf (4.4 N) of pressure on the horse’s mouth, a 2″ shank would need much more rein pressure than an 8″ shank to provide the same effect.

As with many other bits, a pelham may have a solid or a jointed mouthpiece. If solid, it may range from a nearly straight “Mullen” mouthpiece up to a medium port. The pelham’s mouthpiece controls the pressure on the tongue, roof of the mouth, and bars. A mullen mouth places even pressure on the bars and tongue. A port places more pressure on the bars, and provide room for the tongue. A high port may act on the roof of the mouth as it touches, and will act as a fulcrum, amplifying the pressure on the bars of the mouth. Jointed mouthpieces increase the pressure on the bars as the mouthpiece breaks over in a “nutcracker” effect. Unlike a jointed mouthpiece on a snaffle bit, a jointed mouthpiece on a bit with shanks, such as the pelham, can be quite severe in its effect, particularly if the pressure from the shanks causes the joint of the bit to roll forward and press the tip of the joint into the tongue. The mouthpiece is placed lower down in a horse’s mouth than snaffle bits, usually just touching the corners of the mouth without creating a wrinkle. The lower the bit is placed, the more severe it is as the bars of the mouth get thinner and so pressure is more concentrated.

The curb chain applies pressure to the groove under a horse’s chin. It amplifies the pressure on the bars of the horse’s mouth, because when it tightens it acts as a fulcrum. Adjusted correctly, the chain links lie flat and hang loose below the chin groove, coming into action against the jaw only when the shanks have rotated due to rein pressure. The point at which the curb chain engages varies with the individual needs of the horse, but contact at 45 degrees of shank rotation is a common default adjustment.

The Metalab Polo Pelham with 6″ long shanks is one of our favorites for polo. This curb bit is a solid bar with medium port to allow tongue relief while adding some palate pressure. 6 inch cheeks for significant leverage. Curb chain included.

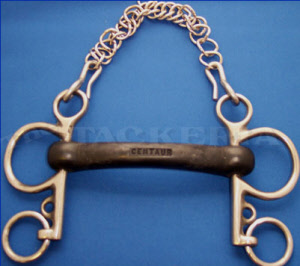

For hunting, we prefer the hard-rubber mouthed Pelham or Vulcanite pelham, which provides good control and is soft on the mouth, particularly in cold weather.

https://www.gavsayspoloacademy.com/blog/how-polo-bits-work

Bar pressure will lift a horse’s head (from snaffle), tongue pressure (from three piece bit) will lower.