from the book of tea, “tea began as a medicine and grew into Beveridge. In China, in the eighth century, entered the realm of poetry as one of the polite amusements. The 15th century saw Japan and Noble it into a religion of a statism, teaism, teaism is a called. Founded on the Dorman of the beautiful among the sword facts of everyday existence. In an ululate purity and harmony, the mystery of mutual charity, the romanticism of the social order. It is essentially a worship of the imperfect, as it is a tender attempt to accomplish something possible in this possible thing we know as life.

At the Denver Botanical Gardens, a Japanese tea ceremony is served at the tea house in the tea garden. The tea house was designed by Dr. Koichi Kawana and constructed in Japan. It was then disassembled and shipped to Denver. A team of Japanese craftsmen carefully rebuilt it.

Okakura wrote The Book of Tea in 1906 in English to convey the spirit of chanoyu to Western readers. Many say that it’s a way of life.TV beginners medicine and grew into a beverage. It is essentially a worship of the imperfect, as if it’s a tender attempt to accomplish something possible in this impossible thing we know of as life.

The Japanese tea ceremony and the Chinese tea ceremony are two distinct cultural practices that revolve around the preparation and consumption of tea, each with its unique customs, aesthetics, and philosophies. Here’s a comparison of the two:

Japanese Tea Ceremony:

- Name: In Japan, the tea ceremony is known as “茶道” (Sadō) or “茶の湯” (Chanoyu), which translates to “The Way of Tea” or “Hot Water for Tea.”

- Philosophy: The Japanese tea ceremony is deeply influenced by Zen Buddhism and emphasizes the principles of harmony, respect, purity, and tranquility. It is a spiritual and meditative practice intended to create a peaceful and mindful environment.

- Focus: The focus of the Japanese tea ceremony is on the preparation and presentation of matcha, a powdered green tea. The ceremony typically takes place in a dedicated tea room or tea house, designed to enhance the aesthetic experience. It celebrates one of the 72 Japanese seasons with a caligraphy and flower arrangement.

- Preparation: The host skillfully prepares the matcha by whisking it with hot water in a special bowl called a “chawan” to produce a frothy and smooth tea.

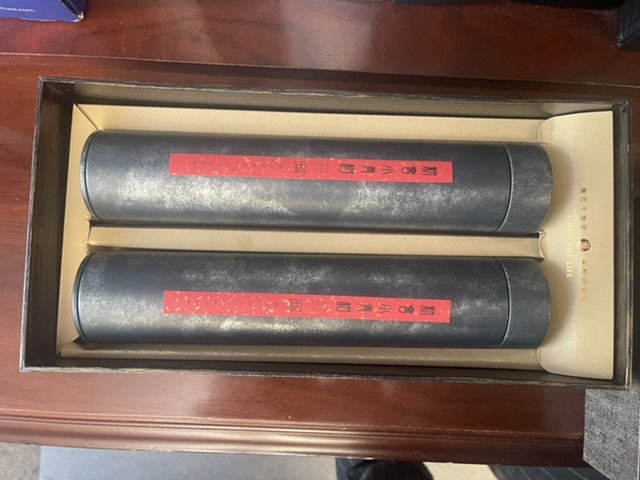

- Kuon (Eternity) 20g – Matcha – Ippodo Tea × 1

- Utensils: Specific utensils, like a bamboo whisk (chasen), tea scoop (chashaku), and tea caddy (natsume), are used in the ceremony.

- Formality: The Japanese tea ceremony can be highly formal and ritualistic, with specific gestures, movements, and prescribed etiquette.

- Guests: The guests in a Japanese tea ceremony play an active role, following certain etiquette in receiving and consuming the tea offered by the host.

Chinese Tea Ceremony:

- Name: The Chinese tea ceremony is known as “茶艺” (Cháyì) or “功夫茶” (Gōngfū Chá), which means “Tea Art” or “Kung Fu Tea” respectively.

- Philosophy: While Chinese tea culture is influenced by various philosophical traditions like Taoism and Confucianism, the focus is more on appreciating the tea’s taste, aroma, and the art of tea-making.

- Focus: Unlike the Japanese tea ceremony, which centers around matcha, the Chinese tea ceremony involves the preparation of loose-leaf teas, such as oolong, green, or pu-erh tea.

- Preparation: In a Chinese tea ceremony, the tea leaves are steeped multiple times in small teapots or gaiwans, with short infusions to extract the tea’s various flavors and aromas.

- Utensils: The Chinese tea ceremony employs various utensils, including teapots, tea cups, a tea boat, and a tea tray. The design and materials of these utensils can vary widely.

- Formality: While Chinese tea ceremonies can be performed in a formal setting, they can also be more casual and adaptable, allowing for personalization based on the preferences of the tea host and guests.

- Guests: In Chinese tea ceremonies, guests may be more passive participants, enjoying the tea served to them by the host, although they may still appreciate and comment on the tea’s qualities.

In summary, both the Japanese tea ceremony and the Chinese tea ceremony are rich cultural practices with different philosophies and rituals. The Japanese tea ceremony emphasizes spirituality, tranquility, and the aesthetics of matcha preparation, while the Chinese tea ceremony focuses on the appreciation of tea’s taste and aroma, often involving multiple infusions of loose-leaf teas.

My Chinese Tea Pots

My tea pots are real from China and probably fetch upwards of $10,000 each now for the two red ones and the brown one with the horse on top, as they are made with zhuni clay. The most expensive pottery is handmade with zhuni clay that has since been mined out in China. The process is much like this one in the following video, it is all done by hand and as you can see it takes a master’s touch and several days to finish one item.

A first (very lengthy, interesting, but sometimes incorrect article) dates the extinction in the 1970s. A more precise date of 1973 is confirmed here (in Chinese). That’s the year when the main mine for zhuni clay got extinct. I write main, because zhuni clay can still be found, albeit in very small quantity, in other Yixing red clay mines. Besides, the extinction is only relative for several reasons:

- like for most natural resources, it’s impossible to tell for sure how much and where there is some left in the ground. With luck, or funds for wide scale exploration, a new zhuni mine may be discovered one day. So far, with other clays available and cheap, there is not enough financial incentive to invest in digging for new zhuni mines

- some potters still have inventories of zhuni clay dating back to before 1973, when zhuni was mined in big quantities.

2. Buyers beware

This means that over 90% of modern zhuni teapots currently on the market are fake. Such teapots are made with a mix of red clay, zisha clay and/or other hard stones. Some unscrupulous business people even add chemicals to the clay. This practice, unfortunately, is not limited to the copying of zhuni but of any kind of yixing teapot.

3. How to distinguish a zhuni from a red clay teapot?

Teaparker showed us the characteristics of a zhuni: under the surface, it’s like there is some sand. It becomes even more apparent when the teapot is warm. This explanation also fits the name zhu-ni, which means red-sand. Let’s notice that the name is not zhu-sha (like in zisha, purple sand). Ni refers to bigger sand like in Nitu (cement), while sha refers to smaller sand like baisha (in white sand beach).

There is much interest in teapots from China and their effect on making tea taste its best. The best of these tea posts are Yixing teapots made from a special rock clay from the Yixing area of China. The best Yixing teapots are called Zisha (Purple Sand Clay, even though they may not necessarily be purple in colour). Zisha teapots are at the heart of the Chinese method of tea-making called Gong Fu Cha (Tea With Great Skill).

How to serve a traditional Chinese tea ceremony.

Unlike western pottery teapots which are made from mud clay and turned on a wheel, Yixing Chinese teapots are assembled piece by piece, either by hand or machine or both. These teapots have excellent porosity and heat handling properties for tea making and as they age, they improve the taste of the teas made with them.

The most rare and special of the Yixing Zisha teapots are known as Zhuni. These teapots are made from clay that comes from a rare rock vein found on some mountain sides and are actually made oversized. They are then fired at a low temperature and for a much longer period than other Zisha teapots. During firing, they shrink to size leaving subtle wrinkles on the clay. This process makes the clay almost glass-like. Most of the teapots break during firing, making the survivors rare and expensive.

Today the markets abound with “Genuine Zhuni Teapots” but it’s all in the definition. During the Ching Dynasty (1644 – 1912 CE), the rare rock was found in a single mountain and Zhuni teapots were exported to Europe. By the mid ‘70’s the rare rock began to run out and since then, three more regions have been used. The clays from each region give the teapots distinctive properties and all can be said to be Zhuni. But amongst serious collectors, only those from the Ching Dynasty period are the real ones. Getting one of those though is almost impossible.

The Anasazi followed a similar style for making handmade bowls, such as this Mesa Verde “duck hunt” replica bowl, made by primative pottery expert, Kelly Magleby. This bowl was made after a bowl residing in the museum at Mesa Verde National Park. The painting depicts a duck hunt with two figures, one with a bow and arrow and the other with a duck call. Pots representing scenes from every day life are rare in the Four Corners Region unlike the mimbres pottery further south. This bowl has striking black on white contrast and turned out just as Kelly Magleby had hoped.

https://www.anasazipottery.net/video

Native Americans had a similar style, which is now best represented in horse hair bowls.

The Japanese folllow a different style for their matcha bowls. All of these are handmade and are very expensive these days, as they were 25 years ago during my Asian travels but have skyrocketed since.

The best tea is found in Hong Kong tea shops such as silver needle and red oolong. And the best pots are only used for one type of tea. The Chinese say a good tea pot can make a good cup of tea, without adding any tea to it, as the patina builds with age over the years.

Kelly says, “The horse is called a “split twig figurine” made by ancient people and probably represent deer or elk. They are occasionally found in caves throughout the southwest. They are made from willow. I know there are a few different ways to make them and there probably are video tutorials. I just got back from a primitive skills gathering where they teach projects like this among other skills like pottery and basketry. Look up rabbitstick gathering, wintercount or firetofire.com”

Japanese tea ceremony

The Japanese tea ceremony (known as sadō/chadō (茶道, ‘The Way of Tea’) or chanoyu (茶の湯)) is a Japanese cultural activity involving the ceremonial preparation and presentation of matcha (抹茶), powdered green tea, the procedure of which is called temae (点前).[1] While in the West it is known as “tea ceremony”, it is seldom ceremonial in practice. Most often tea is served to family, friends, and associates; religious and ceremonial connotations are overstated in western spaces. The English term “Teaism” was coined by Okakura Kakuzō to describe the unique worldview associated with Japanese tea ceremony, as opposed to focusing just on the ceremonial aspect, a perspective that many practitioners frown upon.[2][3][4]

Zen Buddhism was a primary influence in the development of the culture of Japanese tea. Much less commonly, Japanese tea practice uses leaf tea, primarily sencha, a practice known as senchadō (煎茶道, ‘the way of sencha’).

Tea gatherings are classified as either an informal tea gathering (chakai (茶会, ‘tea gathering’)) or a formal tea gathering (chaji (茶事, ‘tea event’)). A chakai is a relatively simple course of hospitality that includes confections, thin tea, and perhaps a light meal. A chaji is a much more formal gathering, usually including a full-course kaiseki meal followed by confections, thick tea, and thin tea. A chaji may last up to four hours.

History[edit]

The first documented evidence of tea in Japan dates to the 9th century. It is found in an entry in the Nihon Kōki having to do with the Buddhist monk Eichū (永忠), who had brought some tea back to Japan on his return from China. The entry states that Eichū personally prepared and served sencha (tea beverage made by steeping tea leaves in hot water) to Emperor Saga, who was on an excursion in Karasaki (in present Shiga Prefecture) in 815. By imperial order in 816, tea plantations began to be cultivated in the Kinki region of Japan.[5] However, the interest in tea in Japan faded after this.[6]

In China, tea had already been known, according to legend, for more than a thousand years. The form of tea popular in China in Eichū’s time was dancha (団茶, “cake tea” or “brick tea”)[7] – tea compressed into a nugget in the same manner as pu-er tea. This then would be ground in a mortar, and the resulting ground tea mixed together with various other herbs and flavourings.[8] The custom of drinking tea, first for medicinal, and then largely for pleasurable reasons, was already widespread throughout China. In the early 9th century, Chinese author Lu Yu wrote The Classic of Tea, a treatise on tea focusing on its cultivation and preparation. Lu Yu’s life had been heavily influenced by Buddhism, particularly the Zen–Chán Buddhist school. His ideas would have a strong influence in the development of the Japanese tea.[9]

Around the end of the 12th century, the style of tea preparation called tencha (点茶), in which powdered matcha was placed into a bowl, hot water added, and the tea and hot water whipped together, was introduced to Japan by Buddhist monk Eisai on his return from China. He also took tea seeds back with him, which eventually produced tea that was considered to be the most superb quality in all of Japan.[10] This powdered green tea was first used in religious rituals in Buddhist monasteries. By the 13th century, when the Kamakura shogunate ruled the nation and tea and the luxuries associated with it became a kind of status symbol among the warrior class, there arose tōcha (闘茶, “tea tasting”) parties wherein contestants could win extravagant prizes for guessing the best quality tea – that was grown in Kyoto, deriving from the seeds that Eisai brought from China.

The next major period in Japanese history was the Muromachi period, pointing to the rise of Kitayama Culture (ja:北山文化, Kitayama bunka), centered around the cultural world of Ashikaga Yoshimitsu and his villa in the northern hills of Kyoto (Kinkaku-ji), and later during this period, the rise of Higashiyama culture, centered around the elegant cultural world of Ashikaga Yoshimasa and his retirement villa in the eastern hills of Kyoto (Ginkaku-ji). This period, approximately 1336 to 1573, saw the budding of what is generally regarded as Japanese traditional culture as it is known today.

The use of Japanese tea developed as a “transformative practice” and began to evolve its own aesthetic, in particular that of wabi-sabi principles. Wabi represents the inner, or spiritual, experiences of human lives. Its original meaning indicated quiet or sober refinement, or subdued taste “characterized by humility, restraint, simplicity, naturalism, profundity, imperfection, and asymmetry” and “emphasizes simple, unadorned objects and architectural space, and celebrates the mellow beauty that time and care impart to materials.”[11]

Sabi, on the other hand, represents the outer, or material side of life. Originally, it meant “worn”, “weathered”, or “decayed”. Particularly among the nobility, understanding emptiness was considered the most effective means to spiritual awakening, while embracing imperfection was honoured as a reminder to cherish one’s unpolished and unfinished nature – considered to be the first step to satori, or enlightenment.[12] Central are the concepts of omotenashi, which revolves around hospitality.

Murata Jukō is known in chanoyu history as an early developer of tea as a spiritual practice. He studied Zen under the monk Ikkyū, who revitalized Zen in the 15th century, and this is considered to have influenced his concept of chanoyu.[13] By the 16th century, tea drinking had spread to all levels of society in Japan. Sen no Rikyū and his work Southern Record, perhaps the best-known – and still revered – historical figure in tea, followed his master Takeno Jōō‘s concept of ichi-go ichi-e, a philosophy that each meeting should be treasured, for it can never be reproduced. His teachings perfected many newly developed forms in architecture and gardens, art, and the full development of the “way of tea”. The principles he set forward – harmony (和, wa), respect (敬, kei), purity (清, sei), and tranquility (寂, jaku) – are still central to tea.[14]

Sen no Rikyū was the leading teamaster of the regent Toyotomi Hideyoshi, who greatly supported him in codifying and spreading the way of tea, also as a means of solidifying his own political power. Hideyoshi’s tastes were influenced by his teamaster, but nevertheless he also had his own ideas to cement his power such as constructing the Golden Tea Room and hosting the Grand Kitano Tea Ceremony in 1587. The symbiotic relationship between politics and tea was at its height. However, it was increasingly at odds with the rustic and simple aesthetics continuously advertised by his tea master, which the regent increasingly saw as a threat to cementing his own power and position, and their once close relationship began to suffer.

In 1590, one of the leading disciples of Rikyu, Yamanoue Sōji, was brutally executed on orders of the regent. One year later the regent ordered his teamaster to commit ritual suicide. The way of tea was never so closely intertwined with politics before or after. After the death of Rikyū, essentially three schools descended from him to continue the tradition. The way of tea continued to spread throughout the country and later developed not only from the court and samurai class, but also towards the townspeople. Many schools of Japanese tea ceremony have evolved through the long history of chadō and are active today.

Venues[edit]

Japanese tea ceremonies are typically conducted in specially constructed spaces or rooms designed for the purpose of tea ceremony. While a purpose-built tatami-floored room is considered the ideal venue, any place where the necessary implements for the making and serving of the tea can be set out and where the host can make the tea in the presence of the seated guest(s) can be used as a venue for tea. For instance, a tea gathering can be held picnic-style in the outdoors, known as nodate (野点). For this occasion a red parasol called nodatekasa (野点傘) is used.

A purpose-built room designed for the wabi style of tea is called a chashitsu, and is ideally 4.5-tatami wide and long in floor area. A purpose-built chashitsu typically has a low ceiling, a hearth built into the floor, an alcove for hanging scrolls and placing other decorative objects, and separate entrances for host and guests. It also has an attached preparation area known as a mizuya.

A 4.5-mat room is considered standard, but smaller and larger rooms are also used. Building materials and decorations are deliberately simple and rustic in wabi style tea rooms. Chashitsu can also refer to free-standing buildings for tea. Known in English as tea houses, such structures may contain several tea rooms of different sizes and styles, dressing and waiting rooms, and other amenities, and be surrounded by a tea garden called a roji.

Seasons[edit]

Seasonality and the changing of the seasons are considered important for enjoyment of tea and tea ceremony. Traditionally, the year is divided by tea practitioners into two main seasons: the sunken hearth (炉, ro) season, constituting the colder months (traditionally November to April), and the brazier (風炉, furo) season, constituting the warmer months (traditionally May to October).

For each season, there are variations in the temae performed and utensils and other equipment used. Ideally, the configuration of the tatami in a 4.5 mat room changes with the season as well.

Thick and thin tea[edit]

There are two main ways of preparing matcha for tea consumption: thick (濃茶, koicha) and thin (薄茶, usucha), with the best quality tea leaves used in preparing thick tea. Historically, the tea leaves used as packing material for the koicha leaves in the tea urn (茶壺, chatsubo) would be served as thin tea. Japanese historical documents about tea that differentiate between usucha and koicha first appear in the Tenmon era (1532–1555).[15] The first documented appearance of the term koicha is in 1575.[16]

As the terms imply, koicha is a thick blend of matcha and hot water that requires about three times as much tea to the equivalent amount of water than usucha. To prepare usucha, matcha and hot water are whipped using the tea whisk (茶筅, chasen), while koicha is kneaded with the whisk to smoothly blend the large amount of powdered tea with the water.

Thin tea is served to each guest in an individual bowl, while one bowl of thick tea is shared among several guests. This style of sharing a bowl of koicha first appeared in historical documents in 1586, and is a method considered to have been invented by Sen no Rikyū.[16]

The most important part of a chaji is the preparation and drinking of koicha, which is followed by usucha. A chakai may involve only the preparation and serving of thin tea (and accompanying confections), representing the more relaxed, finishing portion of a chaji.

Equipment[edit]

The equipment for tea ceremony is called chadōgu (茶道具). A wide range of chadōgu are available and different styles and motifs are used for different events and in different seasons, with most being constructed from carefully crafted bamboo. All the tools for tea are handled with exquisite care, being scrupulously cleaned before and after each use and before storing, with some handled only with gloved hands. Some items, such as the tea storage jar (known as chigusa), are so revered, that historically, they were given proper names like people, and were admired and documented by multiple diarists.[17] The honorary title Senke Jusshoku is given to the ten artisans that provide the utensils for the events held by the three primary iemoto Schools of Japanese tea known as the san-senke.[18]

Some of the more essential components of tea ceremony are:

- Chakin (茶巾)

- The chakin is a small rectangular white linen or hemp cloth mainly used to wipe the tea bowl.

- Chasen (茶筅, tea whisk)

- This is the implement used to mix the powdered tea with the hot water. Tea whisks are carved from a single piece of bamboo. There are various types. Tea whisks quickly become worn and damaged with use, and the host should use a new one when holding a chakai or chaji.

- Chashaku (茶杓, tea scoop)

- Tea scoops generally are carved from a single piece of bamboo, although they may also be made of ivory or wood. They are used to scoop tea from the tea caddy into the tea bowl. Bamboo tea scoops in the most casual style have a nodule in the approximate center. Larger scoops are used to transfer tea into the tea caddy in the mizuya (preparation area), but these are not seen by guests. Different styles and colours are used in various tea traditions.

- Chawan (茶碗, tea bowl)

- Tea bowls are available in a wide range of sizes and styles, and different styles are used for thick and thin tea. Shallow bowls, which allow the tea to cool rapidly, are used in summer; deep bowls are used in winter. Bowls are frequently named by their creators or owners, or by a tea master. Bowls over four hundred years old are in use today, but only on unusually special occasions. The best bowls are thrown by hand, and some bowls are extremely valuable. Irregularities and imperfections are prized: they are often featured prominently as the “front” of the bowl.

- Natsume/Chaire (棗・茶入, tea caddy)

- The small lidded container in which the powdered tea is placed for use in the tea-making procedure ([お]手前; [お]点前; [御]手前, [o]temae). The natsume is usually employed for usucha and the chaire for koicha.

Procedures[edit]

Procedures vary from school to school, and with the time of year, time of day, venue, and other considerations. The noon tea gathering of one host and a maximum of five guests is considered the most formal chaji. The following is a general description of a noon chaji held in the cool weather season at a purpose-built tea house.

The guests arrive a little before the appointed time and enter an interior waiting room, where they store unneeded items such as coats, and put on fresh tabi socks. Ideally, the waiting room has a tatami floor and an alcove (tokonoma), in which is displayed a hanging scroll which may allude to the season, the theme of the chaji, or some other appropriate theme.

The guests are served a cup of the hot water, kombu tea, roasted barley tea, or sakurayu. When all the guests have arrived and finished their preparations, they proceed to the outdoor waiting bench in the roji, where they remain until summoned by the host.

Following a silent bow between host and guests, the guests proceed in order to a tsukubai (stone basin) where they ritually purify themselves by washing their hands and rinsing their mouths with water, and then continue along the roji to the tea house. They remove their footwear and enter the tea room through a small “crawling-in” door (nijiri-guchi), and proceed to view the items placed in the tokonoma and any tea equipment placed ready in the room, and are then seated seiza-style on the tatami in order of prestige.

When the last guest has taken their place, they close the door with an audible sound to alert the host, who enters the tea room and welcomes each guest, and then answers questions posed by the first guest about the scroll and other items.

The chaji begins in the cool months with the laying of the charcoal fire which is used to heat the water. Following this, guests are served a meal in several courses accompanied by sake and followed by a small sweet (wagashi) eaten from special paper called kaishi (懐紙), which each guest carries, often in a decorative wallet or tucked into the breast of the kimono.[19] After the meal, there is a break called a nakadachi (中立ち) during which the guests return to the waiting shelter until summoned again by the host, who uses the break to sweep the tea room, take down the scroll and replace it with a flower arrangement, open the tea room’s shutters, and make preparations for serving the tea.

Having been summoned back to the tea room by the sound of a bell or gong rung in prescribed ways, the guests again purify themselves and examine the items placed in the tea room. The host then enters, ritually cleanses each utensil – including the tea bowl, whisk, and tea scoop – in the presence of the guests in a precise order and using prescribed motions, and places them in an exact arrangement according to the particular temae procedure being performed. When the preparation of the utensils is complete, the host prepares thick tea.

Bows are exchanged between the host and the guest receiving the tea. The guest then bows to the second guest, and raises the bowl in a gesture of respect to the host. The guest rotates the bowl to avoid drinking from its front, takes a sip, and compliments the host on the tea. After taking a few sips, the guest wipes clean the rim of the bowl and passes it to the second guest. The procedure is repeated until all guests have taken tea from the same bowl; each guest then has an opportunity to admire the bowl before it is returned to the host, who then cleanses the equipment and leaves the tea room.

The host then rekindles the fire and adds more charcoal. This signifies a change from the more formal portion of the gathering to the more casual portion, and the host will return to the tea room to bring in a smoking set (タバコ盆, tabako-bon) and more confections, usually higashi, to accompany the thin tea, and possibly cushions for the guests’ comfort.

The host will then proceed with the preparation of an individual bowl of thin tea to be served to each guest. While in earlier portions of the gathering conversation is limited to a few formal comments exchanged between the first guest and the host, in the usucha portion, after a similar ritual exchange, the guests may engage in casual conversation.

After all the guests have taken tea, the host cleans the utensils in preparation for putting them away. The guest of honour will request that the host allow the guests to examine some of the utensils, and each guest in turn examines each item, including the tea caddy and the tea scoop. (This examination is done to show respect and admiration for the host.)[20] The items are treated with extreme care and reverence as they may be priceless, irreplaceable, handmade antiques, and guests often use a special brocaded cloth to handle them.

The host then collects the utensils, and the guests leave the tea house. The host bows from the door, and the gathering is over. A tea gathering can last up to four hours, depending on the type of occasion performed, the number of guests, and the types of meal and tea served.

Types[edit]

Every action in chadō – how a kettle is used, how a teacup is examined, how tea is scooped into a cup – is performed in a very specific way, and may be thought of as a procedure or technique. The procedures performed in chadō are known collectively as temae. The act of performing these procedures during a chaji is called “doing temae“.

There are many styles of temae, depending upon the school, occasion, season, setting, equipment, and countless other possible factors. The following is a short, general list of common types of temae.

Chabako temae[edit]

Chabako temae (茶箱手前) is so called because the equipment is removed from and then replaced into a special box known as a chabako (茶箱, lit. ’tea box’). Chabako developed as a convenient way to prepare the necessary equipment for making tea outdoors. The basic equipment contained in the chabako are the tea bowl, tea whisk (kept in a special container), tea scoop and tea caddy, and linen wiping cloth in a special container, as well as a container for little candy-like sweets. Many of the items are smaller than usual, to fit in the box. This gathering takes approximately 35–40 minutes.

Hakobi temae[edit]

Hakobi temae (運び手前) is so called because, except for the hot water kettle (and brazier if a sunken hearth is not being used), the essential items for the tea-making, including even the fresh water container, are carried into the tea room by the host as a part of the temae. In other temae, the water jar and perhaps other items, depending upon the style of temae, are placed in the tea room before the guests enter.

Obon temae[edit]

Obon temae (お盆手前), bon temae (盆手前), or bonryaku temae (盆略手前) is a simple procedure for making usucha (thin tea). The tea bowl, tea whisk, tea scoop, chakin and tea caddy are placed on a tray, and the hot water is prepared in a kettle called a tetsubin, which is heated on a brazier. This is usually the first temae learned, and is the easiest to perform, requiring neither much specialized equipment nor a lot of time to complete. It may easily be done sitting at a table, or outdoors, using a thermos pot in place of the tetsubin and portable hearth.

Ryūrei[edit]

In the ryūrei (立礼) style, the tea is prepared with the host kneeling at a special table, and the guests are also kneeling at tables. It is possible, therefore, for ryūrei-style temae to be conducted nearly anywhere, even outdoors. The name refers to the host’s practice of performing the first and last bows while standing. In ryūrei there is usually an assistant who sits near the host and moves the host’s seat out of the way as needed for standing or sitting. The assistant also serves the tea and sweets to the guests. This procedure originated in the Urasenke school, initially for serving non-Japanese guests who, it was thought, would be more comfortable sitting on chairs.

Essential elements[edit]

Tea room[edit]

The Japanese traditional floor mats, tatami, are used in various ways in tea offerings. Their placement, for example, determines how a person walks through the tea room chashitsu, and the different seating positions.

The use of tatami flooring has influenced the development of tea. For instance, when walking on tatami it is customary to shuffle, to avoid causing disturbance. Shuffling forces one to slow down, to maintain erect posture, and to walk quietly, and helps one to maintain balance as the combination of tabi and tatami makes for a slippery surface; it is also a function of wearing kimono, which restricts stride length. One must avoid walking on the joins between mats, one practical reason being that that would tend to damage the tatami. Therefore, tea students are taught to step over such joins when walking in the tea room.

The placement of tatami in tea rooms differs slightly from the normal placement in regular Japanese-style rooms, and may also vary by season (where it is possible to rearrange the mats). In a 4.5 mat room, the mats are placed in a circular pattern around a centre mat. Purpose-built tea rooms have a sunken hearth in the floor which is used in winter. A special tatami is used which has a cut-out section providing access to the hearth. In summer, the hearth is covered either with a small square of extra tatami, or, more commonly, the hearth tatami is replaced with a full mat, totally hiding the hearth.

It is customary to avoid stepping on this centre mat whenever possible, as well as to avoid placing the hands palm-down on it, as it functions as a kind of table: tea utensils are placed on it for viewing, and prepared bowls of tea are placed on it for serving to the guests. To avoid stepping on it people may walk around it on the other mats, or shuffle on the hands and knees.

Except when walking, when moving about on the tatami one places one’s closed fists on the mats and uses them to pull oneself forward or push backwards while maintaining a seiza position.

There are dozens of real and imaginary lines that crisscross any tearoom. These are used to determine the exact placement of utensils and myriad other details; when performed by skilled practitioners, the placement of utensils will vary minutely from gathering to gathering. The lines in tatami mats (畳目, tatami-me) are used as one guide for placement, and the joins serve as a demarcation indicating where people should sit.

Tatami provide a more comfortable surface for sitting seiza-style. At certain times of year (primarily during the new year’s festivities) the portions of the tatami where guests sit may be covered with a red felt cloth.

Hanging scroll[edit]

Calligraphy, mainly in the form of hanging scrolls, plays a central role in tea. Scrolls, often written by famous calligraphers or Buddhist monks, are hung in the tokonoma (scroll alcove) of the tea room. They are selected for their appropriateness for the occasion, including the season and the theme of the particular get-together. Calligraphic scrolls may feature well-known sayings, particularly those associated with Buddhism, poems, descriptions of famous places, or words or phrases associated with tea.[21]

Historian and author Haga Kōshirō points out that it is clear from the teachings of Sen no Rikyū recorded in the Nanpō roku that the suitability of any particular scroll for a tea gathering depends not only on the subject of the writing itself but also on the virtue of the writer. Haga points out that Rikyū preferred to hang bokuseki (“ink traces”), the calligraphy of Zen Buddhist priests, in the tea room.[22] A typical example of a hanging scroll in a tea room might have the kanji wa-kei-sei-jaku (和敬清寂, “harmony”, “respect”, “purity” and “tranquility”), expressing the four key principles of the Way of Tea. Some contain only a single character; in summer, kaze (風, “wind”) would be appropriate. Hanging scrolls that feature a painting instead of calligraphy, or a combination of both, are also used. Scrolls are sometimes placed in the waiting room as well.

Flower arrangement[edit]

Chabana (literally “tea flower”) is the simple style of flower arrangement used in tea rooms. Chabana has its roots in ikebana, an older style of Japanese flower arranging, which itself has roots in Shinto and Buddhism.

It evolved from the “free-form” style of ikebana called nageirebana (投げ入れ, “throw-in flowers”), which was used by early tea masters. Chabana is said, depending upon the source, to have been either developed or championed by Sen no Rikyū. He is said to have taught that chabana should give the viewer the same impression that those flowers naturally would give if they were still growing outdoors, in nature.

Unnatural or out-of-season materials are never used, as well as props and other devices. The containers in which chabana are arranged are referred to generically as hanaire (花入れ). Chabana arrangements typically comprise few items, and little or no filler material. In the summer, when many flowering grasses are in season in Japan, however, it is seasonally appropriate to arrange a number of such flowering grasses in an airy basket-type container. Unlike ikebana (which often uses shallow, wide dishes), tall, narrow hanaire are frequently used in chabana. The containers for the flowers used in tea rooms are typically made from natural materials such as bamboo, as well as metal or ceramic, but rarely glass as ikebana (another flower arrangement) uses short, glass vases.

Chabana arrangements are so simple that frequently no more than a single blossom is used; this blossom will invariably lean towards or face the guests.[23]

Meal[edit]

Kaiseki (懐石) or cha-kaiseki (茶懐石) is a meal served in the context of a formal tea function. In cha-kaiseki, only fresh seasonal ingredients are used, prepared in ways that aim to enhance their flavour. Great care is taken in selecting ingredients and types of food, and the finished dishes are carefully presented on serving ware that is chosen to enhance the appearance and seasonal theme of the meal. Dishes are intricately arranged and garnished, often with real edible leaves and flowers that are to help enhance the flavour of the food. Serving ware and garnishes are as much a part of the kaiseki experience as the food; some might argue that the aesthetic experience of seeing the food is even more important than the physical experience of eating it.

Courses are served in small servings in individual dishes. Each diner has a small lacquered tray to themselves; very important people may be provided their own low, lacquered table or several small tables.

Because cha-kaiseki generally follows traditional eating habits in Japan, meat dishes are rare.

Clothing[edit]

|

This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2014)

|

Many of the movements and components of tea ceremonies evolved from the wearing of kimono. For example, certain movements are designed to keep dangling sleeves out of the way or prevent them from becoming dirty. Other motions allow for the straightening of the kimono and the hakama.

Some aspects of tea ceremony – such as the use of silk fukusa cloths – cannot be performed without wearing a kimono and obi, or a belt substitute, as the cloth is folded and tucked into the obi within the ceremony. Other items, such as kaishi, smaller cloths known as kobukusa (小袱紗), and fans, require kimono collars, sleeves and the obi worn with them in order to be used throughout the ceremony; otherwise, a substitute for storing these items on the person must be found.

For this reason, most tea ceremonies are conducted in kimono, and though students may practice wearing Western clothes, students of tea ceremony will need to wear kimono at some point. On formal occasions, the host of the tea ceremony will always wear kimono, and for guests, formal kimono or Western formal wear must be worn. No matter the style of clothing, the attire worn at a tea gathering is usually subdued and conservative, so as not to be distracting.

For women, the type of kimono worn is usually an iromuji – a solid-colour, unpatterned kimono, worn with a nagoya obi in an appropriate tanmono fabric; slub-weave silks, shibori patterns and generally bright-coloured obi are not worn. Edo komon kimono may also be worn, as their patterns are small enough as to be unobtrusive.

Men may wear kimono only, or (for more formal occasions) a combination of kimono and hakama (a long, divided or undivided skirt worn over the kimono). Those who have earned the right may wear a kimono with a jittoku (十徳) or juttoku jacket instead of hakama.

Women wear various styles of kimono depending on the season and the event; women generally do not wear hakama for tea occasions, and do not gain the right to wear a jittoku.

Lined kimono are worn by both men and women in the winter months, and unlined kimono are worn in the summer. For formal occasions, montsuki kimono (紋付着物) (kimono with three to five family crests on the sleeves and back) are worn. Both men and women wear white tabi (divided-toe socks).

Schools[edit]

In Japan, those who wish to study tea ceremony typically join a “circle”, a generic term for a group that meets regularly to participate in a given activity. There are also tea clubs at many junior and high schools, colleges and universities.

Classes may be held at community centres, dedicated tea schools, or at private homes. Tea schools often teach a wide variety of pupils who may study at different times; for example, the school may have a group for women, a group for older students, and a group for younger students. Students normally pay a monthly fee which covers tuition and the use of the school’s (or teacher’s) bowls and other equipment, the tea itself, and the sweets that students serve and eat at every class. Students must be equipped with their own fukusa, fan, kaishi paper, and kobukusa, as well as their own wallet in which to place these items.

Though some groups and practitioners of tea ceremony may wear Western clothing, for most occasions of tea ceremony – particularly if the teacher is highly ranked within the tradition – wearing kimono is mostly considered essential, in particular for women. In some cases, advanced students may be given permission to wear the school’s mark in place of the usual family crests on formal kimono. This permission usually accompanies the granting of a chamei, or “tea name”, to the student.

New students typically begin by observing more advanced students as they practice. New students may be taught mostly by more advanced students; the most advanced students are taught exclusively by the teacher. The first things new students learn are how to correctly open and close sliding doors, how to walk on tatami, how to enter and exit the tea room, how to bow and to whom and when to do so, how to wash, store and care for the various equipment, how to fold the fukusa, how to ritually clean tea equipment, and how to wash and fold chakin. As they master these essential steps, students are also taught how to behave as a guest at tea ceremonies: the correct words to say, how to handle bowls, how to drink tea and eat sweets, how to use paper and sweet-picks, and myriad other details.

As they master the basics, students will be instructed on how to prepare the powdered tea for use, how to fill the tea caddy, and finally, how to measure the tea and water and whisk it to the proper consistency. Once these basic steps have been mastered, students begin to practice the simplest temae, typically beginning with O-bon temae. Only when the first offering has been mastered will students move on. Study is through observation and hands on practice; students do not often take notes, and many teachers discourage the practice of note-taking.

As they master each offering, some schools and teachers present students with certificates at a formal ceremony. According to the school, this certificate may warrant that the student has mastered a given temae, or may give the student permission to begin studying a given temae. Acquiring such certificates is often very costly; the student typically must not only pay for the preparation of the certificate itself and for participating in the gathering during which it is bestowed, but is also expected to thank the teacher by presenting him or her with a gift of money. The cost of acquiring certificates increases as the student’s level increases.

Typically, each class ends with the whole group being given brief instruction by the main teacher, usually concerning the contents of the tokonoma (the scroll alcove, which typically features a hanging scroll (usually with calligraphy), a flower arrangement, and occasionally other objects as well) and the sweets that have been served that day. Related topics include incense and kimono, or comments on seasonal variations in equipment or offerings.

Senchadō[edit]

Like the formal traditions of matcha, there are formal traditions of sencha, distinguished as senchadō, typically involving the high-grade gyokuro class of sencha. This offering, more Chinese in style, was introduced to Japan in the 17th century by Ingen, the founder of the Ōbaku school of Zen Buddhism, also more Chinese in style than earlier schools. In the 18th century, it was popularized by the Ōbaku monk Baisao, who sold tea in Kyoto, and later came to be regarded as the first sencha master.[24][25] It remains associated with the Ōbaku school, and the head temple of Manpuku-ji hosts regular sencha tea conventions.

See also[edit]

- Higashiyama culture in Muromachi period

- Japanese tea classics

- Japanese tea utensils, for a full list of utensils used in Japanese tea

- Matcha, for information about the tea itself

- Wabi-sabi

- East Asian tea ceremony, for tea ceremony in East Asian culture as a whole

- Tea ware

References[edit]

- ^ Surak, Kristin (2013). Making Tea, Making Japan: Cultural Nationalism in Practice. Stanford: Stanford University Press. p. 272. ISBN 978-0-8047-7867-1.

- ^ “There’s No Such Thing as “Tea Ceremony””. 22 April 2021.

- ^ “Do you know the Japanese Tea Ceremony? | RESOBOX”. 20 May 2014.

- ^ “Japanese Tea Ceremony – JAPANESE GREEN TEA | HIBIKI-AN”.

- ^ Kaisen Iguchi; Sōkō Sue; Fukutarō Nagashima, eds. (2002). “Eichū”. Genshoku Chadō Daijiten (in Japanese) (19 ed.). Tankōsha (ja:淡交社). OCLC 62712752.

- ^ Kaisen Iguchi; Sōkō Sue; Fukutarō Nagashima, eds. (2002). “Eisai”. Genshoku Chadō Daijiten (in Japanese) (19 ed.). Tankōsha (ja:淡交社). OCLC 62712752.

- ^ Yuki. “The Origin of Japanese Tea Ceremony”. Matcha Tea. Archived from the original on 11 June 2018. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- ^ Han Wei (1993). “Tang Dynasty Tea Utensils and Tea Culture” (PDF). Chanoyu Quarterly. Kyoto: Urasenke Foundation of Kyoto (74): 38–58. OCLC 4044546. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-02-08. Retrieved 2012-07-05.

- ^ Sen Sōshitsu XV (1998). The Japanese way of tea: from its origins in China to Sen Rikyū. Trans. Dixon Morris. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. pp. V. ISBN 0-8248-1990-X. Retrieved 2012-07-05.

- ^ Tsutsui, Hiroichi (1996). Tea-drinking Customs in Japan. Seoul: 4th International Tea Culture Festival, Korean Tea Culture Association.

- ^ “Chado, the Way of Tea”. Urasenke Foundation of Seattle. Archived from the original on 2012-07-23. Retrieved 2012-07-13.

- ^ Taro Gold (2004). Living Wabi Sabi: The True Beauty of Your Life. Kansas City, MO: Andrews McMeel Publishing. pp. 19–21. ISBN 0-7407-3960-3.

- ^ Kaisen Iguchi; Sōkō Sue; Fukutarō Nagashima, eds. (2002). “Jukō”. Genshoku Chadō Daijiten (in Japanese) (19 ed.). Tankōsha (ja:淡交社). OCLC 62712752.

- ^ Rupert Cox – The Zen Arts: An Anthropological Study of the Culture of Aesthetic 2013 1136855580 “Jaku is significantly different from the other three principles of the chado: wa, kei and set. These all substantiate the normative procedures of chado. Jaku, on the other hand, is pure creation.”

- ^ Tsuitsui Hiroichi. “Usucha”. Japanese online encyclopedia of Japanese Culture (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 2016-03-23. Retrieved 2012-07-13.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Tsuitsui Hiroichi. “Koicha”. Japanese online encyclopedia of Japanese Culture (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 2016-03-23. Retrieved 2012-07-13.

- ^ Chigusa and the art of tea, exhibit at Arthur Sackler Gallery, Washington DC, Feb 22- July 27, 2014 [1]

- ^ Larking, Matthew (2009-05-15). “A new spirit for tea traditions”. The Japan Times. The Japan Times. Retrieved 3 February 2023.

- ^ “Sequential photos of kaiseki portion of an actual chaji” (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 2011-07-22.

- ^ “The Japanese Tea Ceremony in 6 Steps”. Rivertea Blog. 2013-05-13. Archived from the original on 2019-11-18. Retrieved 2019-11-20.

- ^ Haga Koshiro (1983). “The Appreciation of Zen Scrolls” (PDF). Chanoyu Quarterly. Kyoto: Urasenke Foundation of Kyoto (36): 7–25. OCLC 4044546. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-02-08. Retrieved 2012-07-05.

- ^ Haga Koshiro (1983). “The Appreciation of Zen Scrolls” (PDF). Chanoyu Quarterly. Kyoto: Urasenke Foundation of Kyoto (36): 7–25. OCLC 4044546. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-02-08. Retrieved 2012-07-05.

- ^ “Chabana Exhibition (27 May)”. Embassy of Japan in the UK. 2006. Retrieved 2012-07-13.

- ^ Graham, Patricia Jane (1998), Tea of the Sages: The Art of Sencha, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 978-0-8248-2087-9

- ^ Mair, Victor H.; Hoh, Erling (2009), The True History of Tea, Thames & Hudson, p. 107, ISBN 978-0-500-25146-1

Further reading[edit]

- Elison, George (1983). Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan (Vol. 3 ed.). Tokyo: Kodansha. ISBN 0-87011-623-1. “History of Japan”, section “Azuchi-Momoyama History (1568-1600)”, particularly the part therein on “The Culture of the Period”.

- Freeman, Michael (2007). New Zen: The Tea-Ceremony Room in Modern Japanese Architecture. London: 8 Books. ISBN 978-0-9554322-0-0. Archived from the original on 2018-05-11.

- Honda, Hiromu; Shimazu, Noriki (1993). Vietnamese and Chinese Ceramics Used in the Japanese Tea Ceremony. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-588607-8.

- Kumakura, Isao (2023). Japanese Tea Culture: The Heart and Form of Chanoyu (First English ed.). Tokyo: Japan Publishing Industry Foundation for Culture. ISBN 978-4-86658-111-8.

- Momoyama, Japanese Art in the Age of Grandeur. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. 1975. ISBN 978-0-87099-125-7.

- Morishita, Noriko (2019). Every Day a Good Day: Fifteen lessons I learned about happiness from Japanese tea culture (First English ed.). Tokyo: Japan Publishing Industry Foundation for Culture. ISBN 978-4-86658-062-3.

- Murase, Miyeko, ed. (2003). Turning Point: Oribe and the Arts of Sixteenth-Century Japan. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Okakura, Kakuzo (1977). The Book of Tea. Tokyo: Tuttle. ISBN 9781605061351.

- Pitelka, Morgan (2003). Japanese Tea Culture: Art, History, and Practice. London: RoutledgeCurzon.

- Prideaux, Eric (26 May 2006). “Tea to Soothe the Soul”. The Japan Times. Archived from the original on 2017-03-19.

- Sadler, A.L. (1962). Cha-No-Yu: The Japanese Tea Ceremony. Tokyo: Tuttle.

- Surak, Kristin (2013). Making Tea, Making Japan: Cultural Nationalism in Practice. California: Stanford University Press.

- Tanaka, Seno; Tanaka, Sendo; Reischauer, Edwin O. (2000). The Tea Ceremony (2nd ed.). Tokyo: Kodansha International. ISBN 4-7700-2507-6.

- Tsuji, Kaichi (1981). Kaiseki: Zen Tastes in Japanese Cooking (2nd ed.). Tokyo: Kodansha International. ISBN 0-87011-173-6.